A long, slow saga of first-time house buyers

In 1964 my husband Tony came into an inheritance, enough to put a down-payment on a small row house in a village on the outskirts of London. From first placing a ?50 holding payment on a partially-built structure to actually moving in took seven months. Today, with the purchase, remodeling and/or building of four subsequent houses behind me, I read my letters to parents from that period with wry sympathy, thinking how universal is the impatience of a young couple buying their first house.

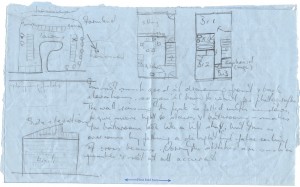

The first letter in the series has a page or more of excited detail.

11 May 1964

… though still with the nagging doubt that it is all too perfect, that something is sure to go wrong. Points in favor: a brand new house within our price range (rare), architect-designed with imagination (also rare), less than a mile from Tony’s job, practically in the country with a charming view over open fields to woodland, closer to London (20 minutes by fast train to Waterloo) and won’t be finished for three months by which time we should have the means to pay for it…. Small, of course, but with ingenious use of space and attractive layout …

When I was growing up, my mother filled binder after binder with house design ideas and plans. We (my parents, three children, and succession of boarders – aunts, uncles, and family friends, often two at a time) lived in a rental Craftsman bungalow built about 1910: two bedrooms and a sleeping porch accessible only through the parents’ bedroom and through a laundry room in which a toilet was installed late in our tenure. (Before that, we used the outhouse back in the yard.) Mum eventually built her dream house when I was about thirteen. In the meantime, I learned a lot about building design and became very familiar with architectural drawing and its symbols. I drew her a sketch:

After a month of marking time, and a thickening correspondence file, a tirade about a building society (English equivalent of a mortgage company) to whom we had applied:

8 June 1964

… the building society wouldn’t consider our house for a mortgage because it was too contemporary in design – they stick doggedly to the deadly dull conventional things. We saw one the other day, part of an estate quite near here – good solid brick, appallingly bad planning, and claustrophobically tiny windows. Mortgages no bother.

A month later, good news on the offer of a loan from another building society. However, letters for the next several weeks report a battle with the developer:

30 July 1964

… One of the hazards of a speculative development – they are very reluctant to depart from the standard model, which in this case is decidedly murky – masses of dark grays, black, browns & blues. I’m getting a bit fed-up – sick of looking at samples & doing sums – I want some action round the place.

8 August 1964

… ran into trouble over the alterations we wanted to the colour scheme – we were met with a blunt ‘take-it-or-leave-it.’ However, eventually Tony rang up & told them they were a lot of bloody-minded so & so’s, & managed to get the most important concession – the colour of the tiles on the floor. The rest of the detailing we shall probably have to rip out & replace as we can afford it. Infuriating, but the housing situation being what it is, we daren’t tell them to go to hell.

Inevitably, construction delays kept postponing the finish date for the house:

26 Sept. 1964

We went up to London on Tuesday to sign the lease & mortgage documents for the house. Exciting, but still somewhat unreal. I am ceasing to believe in the existence of the house, and find it rather unsettling to go over every other weekend or so & find they have done a tiny bit. Still no idea when we can shift in – it will probably be weeks yet.

8 December 1964

It is still hard to believe that we have actually moved in. Up to 9:15 on Friday morning, with the carrier already piling boxes into the van, we still didn’t know if we could – it all depended on the cheque from the building society being in our solicitor’s post. A strange, unreal situation to live through. However, talking to some of the other people who have moved in, they seem to have had much more trouble than us, so we must be thankful.

Anyway, in all the chaos of cancellations, postponements, etc., it was too much trouble to cancel our housewarming party, so we held it as planned on Saturday night. The earliest arrivals were detailed off to put up curtain rails, shift packing cases from the middle to the sides of rooms, etc. Quite a successful party, I think. About a dozen people (& kids) stayed overnight, dossing down wherever for what was left of the night – we got to bed about 4 am, & a few more people dropped in for brunch the next morning. Needless to say by today we are both pretty worn out, but the house is more or less habitable. Strange what an effort, both physical & mental, to make a shell filled with boxes into a habitable room.

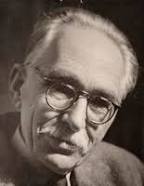

A family of potters

This story starts with a ceramic pot. But which one? Maybe the Lowerdown Pottery bowl I’ve treasured for over fifty years. Or maybe the piece that first inspired Bernard Leach, who is recognized as the “father of British studio pottery,” to take up the craft when he was invited in 1911 to a raku tea party in Japan. The story involves three generations of eminent potters: Bernard Leach, his son David Leach, and his grandson Simon Leach.

In June of 1964, Tony and I went on a vacation with friends to a village in Cornwall where we rented a house. In a letter to parents I wrote:

Yesterday we had quite a big trip – to St. Ives & Lands End. …Arrived at St. Ives in time for lunch – fish & chips in a restaurant overlooking the harbour, watching the tide racing in across the sands. After lunch [our friends] sat on the beach while we explored – delightful little town, all higgildy-piggildy. …On the way out of the town we called at Bernard Leach’s studio… One of the greatest of modern potters.

At the studio we learned that Leach’s son David, who had for many years worked at and managed the St. Ives studio, now had his own pottery at Bovey Tracey in Devon, which happened to be on the back roads route the British Automobile Association had mapped out for us. As we descended from Dartmoor on our way home, there it was: Lowerdown Pottery. David Leach himself greeted us as, children firmly by the hand, we looked around. Although I had very little spare cash, I indulged and bought a pot.

Fast forward forty-nine years. At the urging of our family, Tony and I are trying to putting our affairs in order. We decide to start by making an inventory of our treasures. He photographs, I catalog. We come to the Lowerdown pot. Is it by David Leach or by one of his assistants or students? Its form has affinities with the work of Bernard’s friend Shoji Hamada, who is regarded as one of the most influential masters of studio pottery, and under whose tutelage David first learned the art.

Simon Leach, grandson of Bernard Leach, as shown on the book cover for Simon Leach’s Pottery Handbook—a book-and-DVD package.

By now David Leach has died, but I discover that his son Simon has also become an eminent potter. I find an email address on his website and write to him:

Dear Simon Leach,

About 1964 I visited Lowerdown Pottery and purchased a bowl from your father David Leach that has been a treasured possession ever since. I’m now trying to put my affairs in order for my heirs and am having a little difficulty finding a valuation for this piece — it seems most of his work is now in private collections or museums. It’s stoneware, 5.25 inches in diameter on a narrow foot with his impressed mark on the base. Here’s a picture. If you could give me an estimate of what it’s worth, or where I might turn for this information, I’d be most grateful.

Within a day I receive a gracious reply:

3/5/2013

Hi Maureen

Please send me an image of the seal on the base – clear and in focus also of the other side of the piece.

I will give you an approximate worth if I can.

Best Simon

With the requested images in hand, Simon again responded immediately:

3/6/2013

Hi Maureen

Having seen the seal I see that it is an L+ which means it was made at Lowerdown Pottery.

My father’s work had an Ld to the base. This means that it was not made by him personally…but by an apprentice or other potter there at the time.

Lowerdown pieces with an L+ are of course more plentiful than ones with the Ld so it’s value is somewhat less I would estimate.

I would say it’s value approximately would be in the range 80-100 pounds sterling.

If it had an Ld you might be looking at 250-300 pounds for such a piece.

That is the best I can do for you.

Best Simon

Not only did I have the documented valuation I needed for our inventory. I also had the pleasure of renewing a connection with this family of great British potters.

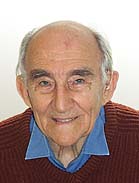

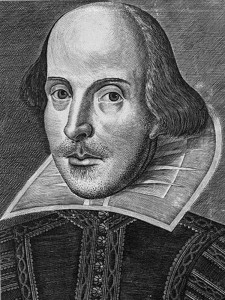

When anger management issues become art

Alec McCowen as the Fool, Paul Scofield as King Lear, RST 1962. Photo from the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive

Even today, the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 1962-64 run of King Lear, directed by Peter Brook, is considered by the company’s actors the finest performance they have ever put on, and Paul Scofield’s role as Lear one of the greatest ever performances of this challenging role. I count myself incredibly lucky to have seen it. Tickets were in such high demand that the theater ran a lottery. Friends scored three of the precious cardboard chits in February 1964 and invited me to join them. Leaving the baby at home with my husband, I eagerly boarded the London train.

I had studied Lear in high school, but it was in the context of cramming for a national scholarship exam. The wild language of the storm scene as Lear descends into madness thrilled me, but I was more concerned with how I would write an essay about “objective correlative,” the idea that the storm as an outward happening can correspond to an inward experience and evoke this experience in the reader. Even so, the play’s themes resonated. At a sheltered seventeen, I knew little about sexual jealousy—married sisters fighting to the death over the attentions of a lover. But I knew about families, that instinctive knowledge about which of their offspring a parent loves the most, and competition for approval from the father.

The plot of Lear interweaves stories of two dysfunctional families: King Lear and his three daughters, the Earl of Gloucester and his two sons. A man prone to towering rages, Lear banishes a devoted daughter who has refused to express her love for him in the flowery language her sisters have used. Lear divides his kingdom between the two remaining daughters, Regan and Goneril, proposing to divide his days between them. Once in power, the daughters try to control him and his retinue. Furious, Lear takes to the outdoors where, in a raging storm, he descends into madness, accompanied by his fool and, in the guise of a madman, Edgar, the elder son of Gloucester, who has been framed by his younger brother Edmund. Meanwhile, Edmund is paying court to both Regan and Goneril. In the end all the principal characters are dead, except for two of the good guys, Edgar of Gloucester and the Duke of Albany, Goneril’s husband. Albany closes the play:

The weight of this sad time we must obey;

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

The oldest hath borne most: we that are young

Shall never see so much, nor live so long.

Paul Scofield was breathtaking as Lear. On the Shakespeare Blog I found quotes from reviews of the time:

Scofield’s gravelly voice found its perfect setting in the harshness of Brook’s King Lear. The Daily Telegraph review of the stage production commented on his “unsentimental, awesome, rasping delivery” and the depiction of a “society only one degree removed from savagery”. The Times commented on his “grating low tones, the powerful air of authority”.

I missed the last train back home to Windsor. Curled up with a blanket on my friends’ couch, I could not sleep. I watched the glowing embers of their hearth fire fade to black as I replayed over and over the intense emotions of this great performance.

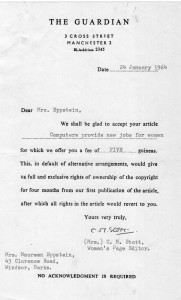

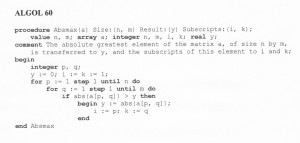

When programming was a women’s job

Back in the day when computer programming as a profession was so new it lacked a gender bias and could well have become a female specialty, I wrote an article about a woman programmer which helped launch a successful freelance business staffed almost entirely by stay-at-home mothers. For me too, it was a big breakthrough: the story was published by the Guardian newspaper on 31 Jan. 1964 under the headline “Computers provide new jobs for women.”

I first met Stephanie (Steve) Shirley in 1963, when our same-age babies were tiny. We had a pleasant chat about what intellectually stimulating work programming was. Frustrated with the sexism that prevailed in the world of employment, Steve had left her job with Computer Developments, Ltd., to start her own company, Freelance Programmers. Her workload was growing as new clients learned of her services, and she was starting to reach out to other former programmers for help.

In a letter to parents a week after the article was published, I wrote:

… My article was published in the Guardian, and since then I have had a flood of letters. Mainly for forwarding to the woman mentioned in it, a computer programmer, retired with a baby the same age as ours, who is trying to get other women like herself to join her in working on a free lance basis.

Less than a year after my first article, the Guardian published my follow-up. Freelance Programming Ltd. was launched. Over time it grew to 8,000 employees, and Dame Stephanie Shirley is now recognized as a pioneer of the British information technology industry. Here’s the follow-up article:

Computer women

In January of this year Mrs Steve Shirley was working quietly at home making up computer programmes in between caring for her baby and doing her housework. Now she has found herself the head of a company employing upward of twenty retired, home-bound programmers like herself. Like many businesses, it started in a very small way. When she retired from her job as a programmer with a big computer company, she was offered a few programming projects to keep her occupied at home. She could work at them in a leisurely fashion, enjoying the contrast between the stark, modern, technical world of computers and the idyllic charm of her cottage in the Chilterns. In this way she found a mental satisfaction that had not been fully achieved in caring for her home and family.

As her circle of clients widened, she was considering seeking out other retired programmers like herself who could help with the load of work. Then a Guardian article on programming as a career for women [my first article] brought in a flood of letters from women who were desperately needing something more stimulating to do with their time. Many were very highly qualified, but because of their children could not consider going back to a job that wanted them on an all-or-nothing basis.

There are some obvious difficulties in running a part-time business of this kind, and Freelance Programmers Ltd. is now having to face some of them. The first is one of organisation. To get a reasonable standard of efficiency, Mrs Shirley had to eliminate those applicants who did not have access to a telephone. The business is at present being run from the cottage, where the telephone rings at all hours of the day and night, and Mrs Shirley herself works very long hours keeping in touch with her staff. In order to get back herself to the part-time basis which would give her time for her family, she plans to open a central office. Here she would be able to employ a typist—at present she does the typing herself, or sends it out to one of her staff, thus making a two-day time lag. The office will be in an area where some of the staff are already living, and her plans are for a combined office and nursery suite, so that the mothers who come to the office will have the children cared for, but will be at hand if needed.

There will still be many of the staff working by themselves at home. Some of them are doing it because they need the money, but for the great majority it is a release from the pressure of four walls and a roof and a tedious round of housework. Mrs Shirley has proved that this method can be made to work, particularly for fairly short-term projects. A larger job, that might take perhaps two years to complete, she prefers to give to women less tied to family responsibilities.

She also needs more free women for the large amount of travelling and meeting clients involved in the business. An ideal staff member is a woman with no children, who is married to a schoolteacher. She had been unable to get a normal job because she wanted all the school holidays off to be with her husband, and not just the regulation three weeks. But for several months at a stretch she is free to go anywhere, do anything for the company.

It has become clear that an entirely homebound, part-time organisation will not work satisfactorily. But a group that is basically of this sort, with a leavening of more mobile staff and with an efficient central organisation, may well be a model on which similar groups of professionally trained women might be based.

Ducks and swans and boats, oh my!

My son’s first word was “duck.” This is not surprising. We lived in Windsor, England, downhill from Windsor Castle and a few blocks from the River Thames, a destination for our daily walk.

There was always something to see on the river. Sometimes rowing crews from Eton College, eight oarsmen in a long narrow shell sweeping the water with long strokes, the cox calling the rhythm. Lots of boats. My family’s special favorite was the elegant “Esperanza,” one of the many riverboats that took visitors on trips upriver.

David’s favorites were the ducks. There were hundreds of them on the river, dabbling among the water weeds, bobbing under with their tails in the air, or clustered enthusiastically close to the walkway if we remembered to bring stale bread to throw to them.

The swans were more scary. They were big, and their large beaks looked ready to take a nip if they were feeling feisty.

The swans of course are famous. Some of the mute swans on the Thames belong to the Queen, others to two ancient guilds, the Vintners and the Dyers. Each year, toward the end of July, there occurs a ceremony called Swan Upping, during which Thames swans with cygnets are rounded up by official Swan Uppers, caught, checked for health, marked with the appropriate leg rings, and then released under the direction of the Swan Marker.

Swan Upper with swan. Photo by Bill Tyne, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29175336

Every day, something new to see.

Pregnancy under a national health system

My old black filing cabinet has yielded up a statistical treasure: an article I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper about the National Health Service’s maternity benefit program in England in 1963. I was pregnant at the time, and financially stressed, so the detailed information was particularly relevant to me. I was also young and impatient with bureaucracy, hence my railing about what seemed excessive form-filling. Keep in mind that the British pound numbers need to be multiplied by 30 to get an approximate equivalent in current US dollars.

A CHILD OF THE WELFARE STATE

Having a baby in England is a (welfare) state occasion. From the moment that a pregnancy is confirmed, an expectant mother can expect to be cared for by the state in practically every detail, down to a monetary allowance for buying clothes.

The services provided are similar in many respects to those in New Zealand [which also has a national health system]. The main difference seems to lie in the number of forms requiring to be filled out for every aspect of care. When she goes to her doctor, the woman will have already filled out a form applying to be placed on the doctor’s list, and she will have received a national health card, which she presents at each visit.

It will have to be decided where the baby is to be born. Unlike New Zealand, where admission to a maternity hospital is practically automatic, most babies in Britain are born at home. Recent reports have suggested that the infant mortality rate could be greatly reduced if more babies were born in hospital, but this raises the problem of inadequate bed space. Some effort is being made by the government to increase the number of hospitals, but it is clear that for many years yet admission to a maternity unit will be restricted to those who have good medical reasons for being there. Next in order of preference are those whose homes are inadequately provided with such facilities as running water. It is usually considered advantageous to have a first baby in hospital, although this is not always possible, and space is provided where possible for mothers having their fourth or later children.

If the baby is to be born at home, ante-natal care is provided by the family doctor and the midwife who will be attending. If the mother is granted a place in a hospital, she goes to the clinic which is run by a team of doctors and nurses from the hospital. Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages. Expert specialised attention is given at the clinics, compared with a family doctor who may, or may not, be deeply interested in obstetrics. Against this are the advantages of seeing the same person at each visit. It is quite possible to see a different doctor at each visit to a large clinic, with the resultant irritating repetition of questions. This lack of rapport, as well as the great pressure of time on the clinics, hinders many women from asking the questions that may be troubling them. The government recently released plans to set up more clinics, which may relieve the pressure a little, but it is difficult to see how much of the mass-production atmosphere can be avoided.

During her pregnancy a mother is provided with several benefits from the state. She receives free dental treatment: normally dental patients contribute the first ?1 of their dental bills, and the health service pays the rest. She receives welfare foods—a pint of milk a day at about half price during her pregnancy, and until her child is five years old. The health service’s own brand of dried milk is provided where necessary. She is also offered cheap orange juice, cod liver oil, or vitamin A and D tablets. These products are free to those who apply to the National Assistance Board claiming hardship.

The state also provides cash benefits. To allay the hardship often suffered when a married woman gives up her job to have her first baby, and to make it easier for her, in the interests of herself and her baby, to give up work in good time before the birth, the state pays her an allowance of ?3 7s 6d a week. To qualify, she must have been paying the full rate of national insurance. It should be explained that health benefits are not paid directly from taxation, as in New Zealand, but from regular weekly contributions to a national insurance scheme. It is possible for a woman, when she marries, to contribute only a nominal sum to the scheme, and to claim on her husband’s contributions for medical benefits. However, if she chooses, she can continue to pay at the single rate, and thus become eligible for these extra benefits.

All mothers, whether working or not, are given a cash grant of ?16 to help with the general expenses of having a baby. A further sum is paid if more than one child is born. In addition to this, those women who have their babies at home are given a home confinement grant of ?6 towards the extra equipment needed.

Needless to say, all these benefits depend on the filling in of forms, and presenting them at the right time. The time limit for each benefit varies, but local national insurance offices are usually helpful about coping with the confusion.

Once the baby is born, the state’s child welfare service, under the local Medical Officers of Health, takes over. This provides a service similar to New Zealand’s Plunket Society, on a nationalised level. The child welfare service is notified by the hospital or midwife of the birth, and within a few days a health visitor calls to take particulars. (Why do they always want to know the husband’s occupation?) She also gives details of the local child welfare clinic, which provides a weighing service, and advice on feeding and other problems.

Home help services are also provided, to look after children while the mother is in hospital, or to help the mother in the home.

For those who can afford to dislike the mass production methods of the national health service, there is an alternative in private treatment. Private maternity hospitals are not subsidised as they are in New Zealand, and attention by an obstetrics specialist and delivery in a private hospital would cost at least ?100 in England, and probably much more. But even with private attention, the patient is still entitled to the maternity grants and welfare foods.

A Shakespearean ghost and an old tree

Herne’s Oak, Windsor Park circa 1799

Etching with hand colouring, attributed to Samuel Ireland (1744-1800). The two Merry Wives of Windsor, Mistress Page and Mistress Ford, are standing with Falstaff at Herne’s Oak.

Drawings Gallery, Windsor Castle

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

In the grounds of Windsor Castle in England stand thousand-year-old oaks so huge and gnarled and blasted it’s easy to imagine them haunted by spirits. Shakespeare used this conceit in his play “The Merry Wives of Windsor.”

When I was a Windsor wife in the early 1960s , I attended a performance by the Windsor Repertory Theatre of “Merry Wives” one summer evening in the castle gardens. Probably written to amuse Queen Elizabeth I, the play uses as its setting then-familiar Windsor landmarks, such as the 14th century Garter Inn on High Street and Herne’s Oak in Windsor Great Park.

The play centers around the drinker and gambler Sir John Falstaff, known from the plays Henry IV part 1 and part 2. Short of money, he comes to Windsor where he attempts to seduce both Mistress Page and Mistress Ford in hope that at least one of them will share her husband’s wealth with him. He writes each wife an identical letter, but the two women, who are close friends, immediately show each other their letters and are outraged.

The wives decide to teach Falstaff a lesson, and pretend to lead him on while planning his downfall. He is dumped from a laundry basket into the muddy River Thames, and beaten while disguised as the Old Woman of Brentford, who is believed to be a witch. With their husbands in on the secret, they concoct a final revenge for his clumsy insults to their virtue. Mistress Page sets the scene:

There is an old tale goes that Herne the hunter,

Sometime a keeper here in Windsor Forest,

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight,

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg’d horns;

And there he blasts the tree, and takes the cattle,

And makes milch-kine yield blood, and shakes a chain

In a most hideous and dreadful manner.

You have heard of such a spirit, and well you know

The superstitious idle-headed eld

Receiv’d, and did deliver to our age,

This tale of Herne the hunter for a truth.

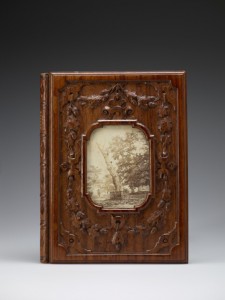

Cover of William Perry’s “A Treatise on the Identity of Herne’s Oak, Shewing the Maiden Tree to Have Been the Real One”

Probably presented to Queen Victoria by William Perry, c. 1867

Drawings Gallery, Windsor Castle

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

The Royal Collection website notes:

Perry’s treatise claiming the authenticity of this tree echoed Queen Victoria’s own belief, though his view was not entirely unbiased since he had been given portions of the wood to carve into souvenirs, which include the binding of this book. A photograph of the tree shortly before its fall is inserted in the front board.

Falstaff is induced to dress as the ghost of Herne the Hunter and wait for the two women at Herne’s Oak, where he is pinched and tormented by local children dressed up as fairies.

Since Herne’s Oak has now fallen, exactly which tree it was—the one that fell in 1799 or the one in 1863—remains in dispute. Also unclear and undocumented are the origins of the myths about Herne the Hunter. Shakespeare was the first writer to mention him. His purported connection to ancient archetypes representing the primal power of nature may be an artifact of Victorian story-makers. Some evidence suggests there was a real game-keeper in Windsor Great Park named Herne or Horne, possibly in Elizabeth I’s time, possibly earlier, who, having committed some great offence for which he feared a dreadful punishment, hanged himself on an oak tree. Maybe Mistress Page had it right: the memory of such an event at a scary-looking tree could be enough to start a legend about a ghost.

My first cuckoo

Sumer is icumen in

Lhude sing cuccu

Listen to this Medieval rote song

An English oak woodland. Image from Open University on the BBC

My first spring in England, late afternoon in Windsor Great Park. Green-gold light through ancient oaks, the air rich with leaf-mold and violets. A cuckoo calls. I have heard the sound all my life, in music and poems, but never before in the wild.

Listen to the cuckoo calling in this recording from the British Library

As I stand listening, this spring in 1962, something shifts in my thinking. It is as if previously I saw the world through two mesh screens, one named Southern Hemisphere and the other Northern Hemisphere, half a year out of alignment with each other, so that my view was blurred by the moiré patterns their meshes made. The religious festivals my ancestors brought from the northern hemisphere when they emigrated to New Zealand lost their old association with the seasonal cycles of life and death when celebrated in the reversed seasons of the southern hemisphere. In consequence, I felt, even as a child, a subtle sense of having been cut off at the roots, of being, even after several generations, transplanted British.

Images float into my mind. Mid-morning, Christmas Eve, at All Saints Church in Tauranga, NZ. Strewn mounds of flowers deck the chancel steps. The Altar Guild ladies are filling shiny brass vases that stand either side of a red-draped altar. Bronze-purple foliage of copper beech, fans of gladiolus spikes, the tropical exuberance of canna. They add dahlias, roses, bougainvillea until the reds vibrate.

Sunlight through stained glass glitters on the sharp points of holly springs that I strew along the dark wood windowsills, hiding jam jars filled with red geranium flowers. The holly bears no berry here, this time of year, and the carol I hum under my breath echoes in an empty place inside me. Later, at midnight services, the congregation sings of light in darkness and the falling of snow. We emerge to warm air, misty moonlight, and the scent of magnolias. This Christmas is not real, I think to myself. It’s pious make-believe.

Easter: after morning church and family lunch, I gather with siblings and cousins on the porch to smash the Easter eggs we have all been given. Molded of hard sugar, they are pastel pretty, with piped-on decorations of flowers and leaves, the symbols of spring. Having gorged ourselves, we scamper off to scuffle through autumnal leaves.

Cuckoo image from

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

My reading in college, particularly J.G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough, helped me recognize that Christian festivals have pagan roots: the ritual victim dies at planting time; the winter birth is the rebirth of the sun. As the cuckoo calls again, cu-coo, over and over, quietly, the blurred meshes of my hemispheres resolve and I see through: myself and my people bound by tangled apron strings to the life our forbears left, and to the earth itself, an old reality, almost forgotten.

What I learned at Stanford

The New Zealand high school I went to, Tauranga College, recently celebrated its 70th anniversary and hosted a reunion for those who attended the college before 1957, the year it split into two single-sex schools. I was one of four alums invited to give a five-minute talk on some aspect of our lives. I was in prestigious company: an emeritus professor of chemistry, the manager of New Zealand’s cricket team during many of its World Series tours, and a researcher doing impressive work in health economics. I chose to talk about my 20 years as an administrative writer and editor at Stanford University, a relatively low-level job, but one in which I had considerable personal satisfaction.

Later that day, many women came up to me to tell me how much they appreciated my words. “I felt affirmed,” one woman said. Our generation was taught rather firmly that a woman’s role in life was to marry and take care of husband and children. Many of course took on paying jobs and volunteer work, but “women’s work” was not highly valued in that strongly patriarchal society.

Here’s the text of my talk:

What I learned at Stanford

I’m sure most of you have heard of Stanford University. The name might bring to mind words like Silicon Valley, medical breakthroughs, prestigious think tank. There’s another, less visible part of the story: the staff work that keeps the university going.

I’m still amazed at how I found myself there in 1979. I was easing back into the job market after being a home-maker and struggling freelance writer. At a neighborhood gathering, I learned that the Stanford administration had a crisis. The federal government was changing the rules for how to calculate the indirect costs for research contracts and grants. (For instance, how much of the university’s electricity cost can reasonably be charged against a particular contract.) When the finance department and the research department put together task forces to figure out how to implement the new rules, they discovered that the faculty doing the research had no idea what the accountants were talking about. They needed someone to translate accounting-ese into English. Could I do it? my neighbor, a Stanford professor, asked. At that time my accounting knowledge was zilch. But what I did have, as a journalist, was the ability to ask the dumb questions that would get me a highly technical story in everyday language. So I was taken on, and within a couple of weeks was ghost-writing memos for the Controller and the Dean of Research.

I stayed at Stanford for twenty years, working on projects related to administrative systems and policies, and support networks for department administrators. During that time, Stanford administration was going through a sometimes painful transition to the world of computers. Imagine if you will a dark basement in an old stone building. Rows of desks are filled with elderly women, most of whom have been there forever, processing Accounts Payable by hand. They’ve never touched a computer, and they’re terrified.

I was part of a group doing our best to help ease this transition. For instance, when I became editor of Stanford’s annual financial report, the entire $450 million of income and expenditures was typed up and tallied by hand. I brought in someone familiar with a computer spreadsheet program to reduce the manual labor. As editor of administrative policies, I headed up an Information Technology skunk works to fulfill a dream of making all the university’s policy and procedure documentation available online. (This was in the early 1990s, before the World Wide Web took off.) I also designed and implemented support programs to gently persuade computer-phobic department administrators to give up their paper copies and use the new system. These programs were the topic of papers that I presented at national conferences.

Sometimes I would ask myself: Does anyone really understand how much power I have? How is it that I, a relatively low level administrative analyst and editor, am dictating annual report deadlines to Stanford’s prestigious external auditors, or leaning on vice-presidents to update their policies, or even writing the policies for them?

The answer is that there are two kinds of power. One is hierarchical: you’re the boss, so you have the right to tell those under you what to do. The other kind of power is interpersonal: if people trust and respect you, they will willingly help you implement a common goal. I learned at Stanford that trust and respect are really all that matter.

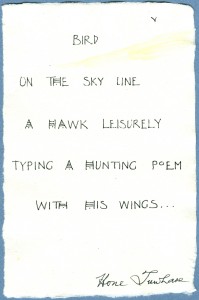

A taonga returns home

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

The manuscript is one my treasured possessions. I have pangs of regret about parting with it, but know I am doing the right thing. In New Zealand Tuwhare’s work is considered a taonga, a treasure. He was the first M?ori poet writing in English to win widespread acclaim. His best-known book, “No Ordinary Sun.” first published in 1964, was reprinted ten times over the next thirty years, becoming one of the most widely read individual collections of poetry in New Zealand history. The title poem is a response to French nuclear testing in the Pacific. Many more collections followed. His work has a conversational tone and incorporates both M?ori and biblical rhythms; the subjects range from the political to the personal and often powerfully evoke the beauties of nature. He won several New Zealand book awards, and was poet laureate of New Zealand in 1999–2000. He died in 2008, at the age of 85.

The M?ori concept of taonga also includes the story that goes along with the item. My little manuscript was a gift from Jean McCormack Tuwhare, Hone’s ex-wife. She and my mother-in-law were friends. On a visit to New Zealand in 2000, I spent a delightful afternoon with Jean at Mother’s house discussing poetry and literature. Mother had shown Jean my first poetry collection, “A Place Called Home,” and later suggested I send her a copy. Enclosed in Jean’s thank-you letter for the book was the Tuwhare manuscript. Unfortunately the letter is lost, but as I recall, Jean wrote that Hone (with whom she was still close friends) liked to practice calligraphy and had given her several of these small pieces to dispose of as she wished. She thought I might appreciate having one.

[Update 6/2/1016: While in New Zealand, I learned from Rob Tuwhare, Hone and Jean’s son, that Jean herself did the calligraphy, and Hone signed her work.]

I am of an age when I need to make decisions about my stuff. Knowing that the manuscript could easily get overlooked among our mountains of paper and art works, I sought professional help. I told Malcolm Moncrief-Spittle of Renaissance Books (New Zealand) , who deals in rare and out-of-print books, that I thought my taonga should be returned to New Zealand. Which university or cultural institution in New Zealand already houses a collection of Tuwhare material and would be a suitable recipient? I asked. He recommended the Hocken Library at the University of Otago in Dunedin.

Staff at the Hocken Library responded to my query with enthusiasm. We’ve arranged a meeting on May 9, when I will hand over the carefully packaged manuscript. I know it will be a happy/sad occasion.