Little boys in their own words

A few months after I interviewed Paul Abbatt, the London toymaker and child development theorist (see my previous blog piece, “An advocate for junk heaps”), I called to ask about his planned survey on what children actually did in their outdoor play. He sighed. The response had been so overwhelming that he’d had to abandon his plans for a detailed analysis. But he did share with me a sampling of the letters he’d received.

The follow-up story I wrote for my New Zealand paper, the Christchurch Press, was published in November 1963. It is transcribed below.

London Children’s Play Survey Abandoned

The publicity given to his proposed survey of the playing habits of British children has resulted in a big problem for the London toymaker, Mr Paul Abbatt. The flood of letters, both from parents and from children, reached such unmanageable proportions that he has had to abandon the detailed analysis he had planned.

But the letters have shown him that many parents and children had common problems. Mothers especially emphasised the need for adequate, and preferably supervised, space for their children to play.

The following is an extract from a letter by a mother of three children, all under five years:–

“It may be of interest for you to know that Crawley is a New Town—the so-called ‘Planner’s Dream.’ It is a ‘Mum’s Nightmare.’ My neighbourhood has no children’s playground, and has not had one for four years. So my children play in the road. Afternoon walks are too often an uninteresting march down roads of which the uniformity is quite paralysing.”

The mother of a boy of eight years says she could do with an attendant in the nearby park, “so that we would not be afraid to let the boy play there alone—an attendant to keep in check the bullying of older boys and help in case of accident with the swings. So, although only 100 yards away, he never goes.”

Many letters from mothers and particularly those from the children, showed children’s love for simple things, and places to make dens. A small boy of 10 gave detailed instructions on how to make a camp in a tree or cave, with the concluding remark: “Then all you need is some things to put in.” Another boy described how he and his friends caught rats on an allotment. A boy of 11 started his letter: “One Saturday when we didn’t know what to do we decided to go on a bike ride.” After several adventures they came to a secret place that one of them knew. “We went down a bank very slowly and we turned into a kind of glade. It was great. There was a stream flowing by and a smashing high tree to climb.”

Looking for the tracks of wild animals was a special memory for one boy, while the letter of another resounded with such names as Steam Engine No. 62004, Class Q.6 and Diesel Deltic, Type 5, No. D9007. Detailed rules for gang warfare were given by another.

The cramped conditions of urban housing are reflected in the letter of a boy whose favourite sport is cricket. He writes: “In summer I play cricket in the back lanes or sometimes I play at the welfare with the lads at school. One night when I came from school I went into the back lane to play cricket with my friends. I said you fetch your bin lid and I will fetch mine. We tost up a coin to see who would bat. After a few minutes a car came round the corner. At seven o’clock my mam came to the door and told me to have a bath. I went in unhappy.

“In the winter when the days are shorter and it’s dark at four o’clock I play football in the lane. Sometimes when it is raining I have a game of football in the yard. One day I kicked the ball that hard, I heard ‘smash’ one pint of milk rolling down the yard.

“Cricket is my best sport. One time my dad was having a game of cricket with me; he was in batting. I bowled, my dad hit it with such a ‘wham’ he smashed the window.”

An advocate for junk heaps

Cover and invoice of a 1964 informational booklet, “Creative Play” published by Paul & Marjorie Abbatt, Ltd. Image from Pinterest

By the time I interviewed him in 1963, Paul Abbatt and his wife Marjorie had spent thirty years as advocates for the importance of play in the development of young children and for the betterment of children’s toys and playing facilities. Toys commissioned by their toy company, Paul and Marjorie Abbatt Ltd. of 94 Wimpole Street in London, won prestigious international awards for their good quality and design. Paul Abbatt, whose chief interest was in ‘the ethos behind the business,’ delivered lectures and contributed to academic and professional journals on child development.

In 1963, Abbatt was focusing on outdoor playgrounds for older children. He commented that

“…as a society becomes more urban and industrialised, it becomes more and more hostile to the child and its needs. As buildings are packed closer and closer together, available sites become too valuable for industry, or for car parks, to be used for children’s playgrounds. Even the upper class child with a garden of his own is no better off, for custom demands that his parents keep their grounds neat and spotless, and the child has no opportunity for such fundamental activities as building a den, or digging down to Australia.

In keeping with the stereotypes of his time, by older children he meant older boys, assuming that a girl would be “already a mother with dolls, kitchen, a little house of her own.” The interview continues:

Mr Abbatt believes that the solution to the needs of the older child can be found in the adventure playground. The first of these was built several years ago in Copenhagen, where the designer, instead of putting in the usual concrete shapes, swings and slides, filled his playground with builders’ junk. The playground was a great success, and was copied all over Europe. Some cities produced old cars, or traction engines, used tires, and even an old boat.

The first experimental playgrounds, with their carefully manufactured playing facilities, had not been a success. The children were interested at first, but quickly gravitated to the streets just outside the playground, where they were closer to the real life that they knew. But when the material was provided on the sites for them to build their own dens, they could create their own world inside the playground. “Building a den seems to be fundamental to children’s play, and other activities develop round the original den,” said Mr Abbatt. In Zurich, for example, the gang who inhabited one playground built up such a community spirit that they had their own bank with its own play money, a duplicated magazine, an antique shop, and even a farm with a dozen ducks on a man-made pond. When each gang deserts the playground, as they eventually do, the dens are pulled down, and the next gang to come along starts from scratch with the pile of junk.

In the meantime, in Copenhagen, the first adventure playground has become something of a showplace for visiting social workers. The grounds have been tidied up, and the rough dens turned into pretty villas. The visitors look and admire, but the children no longer come.

Similar problems affect playgrounds in Britain. They are normally noisy, untidy, derelict places, a disgrace to the neighbourhood of neat houses with even neater gardens. So local residents complain, and the council tidies up the playground. “In doing so, they destroy the urge for creative activity that the previous junk-heap gave to the children,” said Mr Abbatt.

In preparation for a conference of the International Council for Children’s Play, which Abbatt helped found, he is making a descriptive survey of children in Britain.

He has invited parents to write and tell him what their children do, and, since small boys particularly are notoriously uncommunicative about the activities of their gangs, he is also seeking information from policemen, schoolteachers, traffic wardens, and others who see the children outside their homes. Already the response from parents has been overwhelming.

He hopes that the survey will provide town planners, architects, and designers, with information on what children really want out of their community.

In a note to my editor, I promised a follow-up when the survey results were in. I’ll talk about that in my next blog piece.

A nuclear protest in the rain

Participants in the 1963 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament march from London to the nuclear weapons facility at Aldermaston in Windsor High Street. Image by Tony Eppstein.

To walk from London to the UK’s Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston in Berkshire takes four days. Starting in 1958, the year the UK and the US signed a mutual defense agreement “on the uses of Atomic Energy for Mutual Defense Purposes” tens of thousands of people did it over Easter weekend each year, to protest the risks to humankind and to the earth itself from the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

I first watched the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament’s march on Easter Saturday, 1963. Heavily pregnant, I stood with other townsfolk on the sidewalk of Windsor High Street. Rain had fallen all week and continued to fall, a cold, relentless, English rain. About mid-morning the first marchers came, under a sky the same brooding gray as the rain-soaked castle walls above us. Their clothes sodden, they chanted fitfully to the dogged drumbeat of wet shoes on streaming pavement. Some carried banners bearing the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament symbol.

We had a friend in the march. An hour passed before we spotted him, poncho flapping, wet hair plastered to his face. We cheered and called out. He grinned and waved. Another hour or more before the last stragglers passed through the town. We cheered them too. I leaned on my husband’s arm, feeling the weight of the unborn life inside me.

Postscript: organized protests against nuclear weapons in the UK continue to this day. You can see an overview at the Action AWE website.

The last time I saw Paris

An old letter from my black file cabinet brought back memories of a brief vacation in Paris in 1962. Rereading the headlong, crammed-onto-the-page text, I hear again the breathless voice of a wide-eyed young traveler falling in love with the city of light.

I’ve not been back to Paris. It’s likely I never will. But, as in the old Jerome Kern song, I’m happy to remember her as I saw her back then.

Listen to Dame Kiri Te Kanawa

singing “The Last Time I Saw Paris.”

Windsor, 24 Sept

Dear Mum & Dad,

Breakfast tray at our door each morning: croissants with butter and jam, café au lait–the height of luxury.

Back home in England again, and not particularly pleased to be back to these bleak autumnal mists, and a real stinker of a cold to go with it—first cold I have had for ages. We had a wonderful week in Paris, and fell in love with the city. Left very early Monday morning—rose before the sun, about 5 am, and took off at 8 in a Caravelle, a very fast French jet plane, which landed us in Paris before 9 – though it was after 10 by the time we got to our hotel, which was in a little side street off one of the main boulevards. Rather noisy, at least for the first night, as it was close to the great city market, which does its business in the small hours of the morning. The second night we didn’t even notice it. Nice room, with a balcony from which we could watch all the goings-on in the street below—most entertaining. We spent practically every day walking—the number of miles must be pretty high. First morning we went down to the old centre of the city, the Île de la Cité, an island in the Seine, and had a look at Notre-Dame—I hope you got the postcard I sent you of it. Spent the rest of the day pottering round the island, along the banks of the river to the Tuileries, and back by a more or less circular route to the hotel. The next day we went up to the north side of the city, to the hills of Montmartre—fascinating streets, most of them ending in steps, somewhat like parts of Wellington, and with graceful balconied buildings with the plaster peeling off. About midday we went out to the woods of Boulogne, a huge park just out of the city, where we watched workmen playing at bowls in their lunch-hour. It is a sort of grown-up marbles, played with heavy steel balls that you throw to knock out the kitty. Then we went back to the Arc de Triomphe and walked down the Champs Elysees—lots of interesting shops, and the wide street incredibly tightly packed with vehicles—you look down the street and you see nothing but a sea of car roofs. Traffic in Paris is very thick, very, very fast (no speed limits) but amazingly well organized. Pedestrians beware though—they are very much second class citizens, and boy do they hop when the traffic starts to move. Anyway, back to Tuesday—later in the afternoon we went over and had a look at the Eiffel Tower—a remarkable piece of engineering. We didn’t go up it, however—we had already seen enough views of Paris from above, and weren’t very keen on its reputation for swaying.

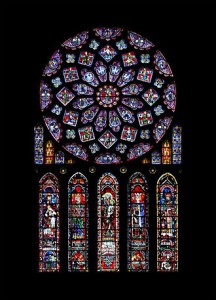

The next day we met my college friend John Wilson, who is at present living in Paris, and he took us out for the day in his little car, one of the new utility model Citroens. You may not have seen them in New Zealand. A chopped-off little bug, a bit ugly, very mass-produced, but able to go anywhere, very cheap, and very comfortable to ride in. There are thousands of them in Paris. Went first to Versailles, to look at the palace where the king and Marie Antoinette were taken from to have their heads chopped off. A most impressive building (though we didn’t have time to go inside), and the gardens are incredibly beautiful, in a cool, formal sort of way. Mostly vistas of fountains and pools, with statues, with a few formal flower beds, and woods beyond, laid out with a grace and elegance unknown to these more democratic times. We could have stayed there just wandering all day, but had to get going again, through side roads and quaint little villages. We had lunch in one, at a street café in the village square, just outside the gates of a very charming old chateau, whose towers were reflected in the canal close by. Then on to Chartres. The cathedral stands on a hill overlooking the plain, where there has been a church since the third century. This one was built in the 13th century, and was remarkable in that, except for part of one tower, which is noticeably odd, it was completed in thirty years. Outside very elaborate and impressive relief carvings in the porches, lots of gargoyles and what not.

You go inside, and it seems at first quite dark. Then gradually, as your eyes get used to the light, the huge pillars begin to appear, lit up by a pale greenish, strangely luminescent glow. Then you look up, and are practically dazzled in the burst of red and blue and green. The stained glass windows of Chartres are said to be the most magnificent in the world, and I can well believe it. To the north, south and west are huge rose windows, and all around are arches, each closely worked with many little pictures of saints, in incredibly fine detail. The result is a blaze of pattern and colour.

Then back the sixty miles to Paris, through wide open fields—no fences in this region, and the land is fairly bare of trees, and with a very gentle swell. It is a grain growing area—lots of harvesting machinery, and everything a beautiful golden colour—even the soil is the same colour as the wheat stubble. The next day we went to the Louvre museum, or at least to a small annexe, the Impressionists gallery—Van Gogh, Renoir and co., and discovered again the beauty of many of the paintings that we had thought a bit hackneyed in reproduction—things like Degas’s ballet pictures for instance—very beautiful and subtle in the originals. Spent all morning there, and in the afternoon walked over to the other side of the city, to see the UNESCO building, a very fine modern building. Our favourite part of it was a Japanese garden in the grounds, a little area of different levels and contrasting textures of stones and gravels, a stream and a pond, and a few bushes. Sounds rather stark and uninteresting to describe, but the result was charming, and very peaceful and relaxing. Friday back to the Louvre, to the main museum this time, but when you think that each of the wings of this is about a mile long, with several intersecting galleries about half a mile across, and all several stories high, you will realise that we didn’t see much of it, and even what we did see—mostly Assyrian, Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, there were so many fascinating and beautiful things to look at that we didn’t do them justice—excuse for going back! Later in the afternoon we had to think of getting ourselves back to the airport. Bought some beautiful (smelly) French cheeses from one of the many street markets, then got out to the airport to catch our plane at seven. Wonderful to see the lights of London as we flew over the city—when we got under the cloud, that is. Very exhausted by the time we got home, but still wouldn’t mind doing it again. Though went into London yesterday, to see [our friend] Bill, an exhibition at the Tate, and a concert at the Festival Hall, and decided that London was rather lovely too.

Vive la France! Love, Maureen

A day at a famous cookery school

Cookbook cover, considerably more pristine than my beat-up copy. Image from http://magazine.direct2florist.com

As an engagement gift, my future mother-in-law gave me a copy of The Constance Spry Cookery Book. Constance Spry was well known in New Zealand, both for this book and for her several books on flower arranging. When I moved to England in the early 1960s, I was delighted to discover that I lived quite close to Winkfield Place, the school of cookery and domestic arts founded by Mrs Spry and Rosemary Hume, who was also co-director of the Cordon Bleu School in London. A hook for a story for my New Zealand paper was that a NZ girl currently attended the school, so I wangled myself an invitation to spend the day. Here’s what resulted:

A day at a famous cookery school

Even at first sight Winkfield Place is charming. It is a large, white country house, set in broad gardens on the edge of Windsor Forest. Inside, all is bustle and activity. About 100 girls are going about their regular classes: cookery, dressmaking, handwork, flower arranging, shorthand and typing, and another 60 local women are attending demonstrations on cookery and flower arranging. The girls normally spend a year at the school, with a few staying on for a fourth term to take the Cordon Bleu diploma, which is recognised all over the world.

The girls, each in shining white overalls and chefs’ caps, cook in classes of 10. From one kitchen came appetizing smells of spaghetti and baked apples. From another, risotto with a potato salad, and a hazel-nut meringue to be served with an apricot sauce. Miss Hume was found in another kitchen busily stirring whipped cream into a creamed rice pudding. A dish of chopped nuts was waiting to be sprinkled on top.

Later in the afternoon, Miss Hume gave a cooking demonstration. Lotte en mayonaise, tourtiere de boeuf, chicken mousse italienne, and chamonix, were the menu for her supper party. Translated, they were a fish mould gaily decorated with gherkins and chopped parsley, a tasty steak pie, a jellied mould of creamed chicken and shredded ham, and a magnificent dessert of meringue topped with a piped “birds nest” of chestnut puree and whipped cream.

Miss Hume is described by Mrs Spry in her book (which is jokingly referred to as “the bible” at Winkfield) as the authority from whom she obtained all the cooking knowledge she had. She is a tall thin woman, with a strong no-nonsense face, a shy smile, and a deft hand with the pastry. Her guiding characteristics are commonsense and a passion for economy: she believes that all food should be treated with respect, and that to waste it is a crime. She has become expert in parrying the comments of the more snobbish of her day class audiences. One woman, for instance, wondered why she did not use fillet steak in her pie, instead of the less expensive, and less tender, rump steak. Her reply was that fillet was too good for this sort of pie, which was a “cut-and-come-again,” and that the recipe called for a cooking time quite adequate to make the rump tender. Her final comment tactfully vanquished the snob. “I for one would be grateful for a piece of this pie,” she said.

The spirit of Mrs Spry lingers throughout the house. Although few of the present students ever met her, many of the staff, who are old girls of the school, recalled her engaging personality. They spoke of the dinner parties she used to hold on the bare scrubbed table of the diploma group’s kitchen, with the candlelight gleaming on the array of copper utensils on the shelf behind. They described with amusement the clutter of treasures in her flat, and the extraordinary leaps of her conversation. “You will remember, dear,” she would whisper confidentially to one of her students, in the middle of a discussion on current affairs, “that you must always clean out the bath when you get out of it, and hang the bathmat up to dry.” Many remembered her beautiful hands, and her great skill with flowers. With it went the ability to encourage her pupils. Mrs Christine Dickie, now co-principal of the school, described how she herself was never very good with flowers. “But Mrs Spry would come in with a great heap of flowers, and say, ‘Do arrange these for me, dear.’ I would struggle with them, but the result always looked a mess, and I would beg her to show me what to do with them. ‘What’s wrong with that, it looks fine,’ she would say, giving the whole bunch a little tug that made it exactly right. Then I would be rather pleased with myself, although I know deep down that she had done it.”

Mrs Dickie was with Mrs Spry during the founding and early growing pains of the school. “She had that wonderful gift of delegating authority,” she said. “She would forge ahead with some new project, with her ‘dogsbody’ (that was me) beside her, and when the groundwork was laid, she would say, ‘Now you take over – I have other things to do’.” The result was that at her death a few years ago, the staff, although they missed her very much, found that they could continue almost as if nothing had happened. Mrs Spry made provision for this in her will. She instructed that the existing staff were to run the school for three years. If they succeeded in keeping it going, they would be permitted to continue, but if in that time the school went downhill, it was to be closed immediately.

It says much for Mrs Spry’s groundwork, and for the enthusiasm that she had inspired in her staff, that not only has the school survived, but it has had to expand to cope with the increasing demand. There is now a long waiting list for places, and the day classes, about 60 women each on three days of the week, are filled well ahead of each term.

There have been a few changes in the character of the school, and these are ones that reflect an interesting facet of English society, the decline of the debutante. When the school opened, it was regarded as a finishing school for debutantes, as a place to acquire some skill in the domestic arts before coming out into society. To a certain extent this is still true, although of the 100 girls at present at the school, only four or five are potential debutantes, and the social whirl of a debutante’s life is viewed with some scorn by the staff. The others will take up a great variety of careers. Some will go from the secretarial course to office jobs. Many of the girls in the cookery course will go into institutional kitchens, some into private houses. Some will take up other careers, such as nursing. The really dedicated cooks are to be found in the Cordon Bleu diploma class, practically all of whom want to be free lance professional cooks, and spend many of their odd moments discussing the most suitable kit of kitchen equipment to carry with them, or the prospect of gaining experience among their friends.

There are still some girls who will probably not have to earn their living. For them the course provides a convenient stop-gap between school and adult life, in a place where they can learn to grow up pleasantly and happily, while at the same time providing themselves with a form of insurance in case they do have to keep themselves. For them it is also a safeguard against the increasing difficulty of finding domestic staff. Coming from homes where all the housework is done by servants, they realise that for themselves it may be a choice between the cooking and the dusting. The girls who attend Winkfield have plumped for the cooking.

Airline pilot: a loyal expat

Among the New Zealanders Abroad series I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper in the 1960s is a lengthy interview with airline pilot Captain Ronald Hartley. His celebrity in 1962 was as commander of the airliner taking Princess Margaret and the Earl of Snowdon to Jamaica for the independence celebrations. Later that decade he flew Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh to Canada.

Princess Margaret dancing with Sir Alexander Bustamente at the Jamaican Independence Day celebrations. From http://blogs.jamaicans.com/

A World War II Royal Air Force hero, Hartley helped form an airline that amalgamated with B.O.A.C. He was one of the first B.O.A.C. pilots to train on Britannia aircraft, and in 1962 was deputy flight manager of the Britannia 102 flight. Much of his work involved the planning of new aircraft, such as the Vickers VC10.

“We are surrounded by experts who know what is possible – it is our job to stand in the middle of the argument and tell them exactly what we require.” In such things as the layout of cockpits pilots can bring practical experience, and Captain Hartley and his colleagues are at present working for a standardization of cockpit design. This is so that a pilot can if necessary step into a strange place and know where all the instruments are likely to be on the panel.

Captain Hartley was born in Auckland in 1909. When he was 19 years old his parents returned to England, taking him with them. Although he never returned to New Zealand, Captain Hartley was still very proud of being a New Zealander.

“There is something about the land of one’s birth that makes you always loyal to her,” he said. He is proud of New Zealand’s social legislation, and the high reputation that New Zealanders have in England, a reputation gained, he thinks, from their service during the two world wars.

His memory of New Zealand is a picture of beaches and bush. “When I was a boy we used to jolt down a dirt road to the beach at Muriwai or Piha, and when we got there we would have the whole place to ourselves – not like the noisy, overcrowded holiday places here in England.” He remembers Boy Scout camps on the shores of Manakau Harbour, with the bush coming down to the water, and long hot summers with warm water for swimming. Now he has a cottage in Devon, but even in mid-summer the water could only be described as “bracing.”

He found the different way of life in England hard to get used to at first. “In my first year I rushed around joining clubs – tennis clubs, athletics clubs, anything to make friends.” He was conscious of the class distinctions in English society. ”It sometimes worried me that I didn’t know much about things like wines, or the right brand of cigars or caviar. Now that I am older, and know more about me, I have learned better.”

He had come to realize that most people needed his help and friendship more than he needed theirs, and he has worked on this assumption throughout his career.

“I have tried to bring up my children the same way too. When they showed signs of shyness at an early age, I used to tell them, if they were going to a party: “Now don’t you dare have a good time until you see some little boy or girl who looks lonely and make friends with him.”

For the new immigrant to England such as myself, his comments about not being able to return permanently to his birthplace were an uncomfortable revelation, and one we quickly discovered for ourselves. He was having too much fun, he said.

“I enjoy dealing with people, and I love the clash of personalities and opinions that you get in such a huge and complex organization as this.”

Postscript: on Nov. 21, 1969, Captain Hartley was killed when as a passenger on a Nigerian Airlines flight, the new Vickers VC10 crashed on its landing approach to Lagos airport.

Coldness depends on what you’re used to

A letter dated April 5, 1963 has set me to thinking about how the human body adapts to temperature differences. Tony and I, and my sister Patricia, who lived with us in Windsor, England, were luxuriating in warmer weather after the Big Freeze, the coldest winter Britain had seen for over 200 years. We’d survived ice-covered walls and windows and frozen pipes, with two paraffin (kerosene) heaters our only source of heat. (There was also a wall-mounted electric heater, but it gobbled shillings and half-crowns as if it were starving.) Then our elder sister, Evelyn, arrived from Syracuse, New York, where she had been completing her doctorate. Her letter to our parents, published in her “Letters From America 1960–1963” (University of Waikato, 2005) tells the story:

I am sitting huddled over the paraffin heater in Maureen’s living room… I am still not acclimatised. This place is so cold and I miss American central heating. Here it is cold both inside and out; there is no escape. I am wearing nearly all the clothes I possess, it seems, and I sleep under a mountain of blankets, but still it is cold. In Syracuse, though it is snowing and below zero outside, once inside we took off all our heavy coats etc. and just a cotton blouse, skirt and sandals were sufficient. I am not used to wearing all these clothes all the time, but I guess, if you live here long enough, you get used to it.

On our way to England the previous March, Tony and I visited that apartment in Syracuse where Evelyn lived with fellow students from South East Asia. Dirty snow lined the streets, the sky was gray, the apartment a stifling 80 degrees.

Evelyn left space in her letter for me to add a paragraph:

…It isn’t really as cold as Evelyn makes out, although today I must admit is rather bitter. But while the rest of us are dehydrating in the hot-house fug inside, she still complains of the cold, so I don’t know what we can do.

Pat, Tony and I would surreptitiously open doors and windows, but nothing could stay open for long. We all suffered.

A little poking around the internet informs me that getting acclimated to temperature differences typically takes about two weeks, a bit longer for adjusting to cold than to heat. This makes it hard for travelers who spend only a few days in one place. People who live in extremely hot or extremely cold climates have adapted over the eons. In arctic areas they have large, compact bodies with relatively small surface areas from which they can lose their internally produced heat. In addition, they have made technological changes such as insulated clothing and houses, and cultural adaptations such as sleeping in a huddle with their bodies next to each other. In hot parts of the world people are more likely to be tall and slender, with low body mass, and to limit their activities to cooler parts of the day.

For the past 15 years I’ve lived in Mendocino, CA, where the average temperature ranges from the mid-40s to the low 60s Farenheit, and 75°F is a hot day. The county seat, Ukiah, where we sometimes have to go for business or medical appointments, is inland, or as we say, “over the hill.” There the summer temperature average is in the mid-90s and my body tells me: Nah, that’s way too hot. How can people stand it?

Plumbing crisis brings neighbors together

Windsor Castle in the snow, January 1963. We lived in the town below the castle. Photo by Tony Eppstein.

The winter of 1962-63, my first in England, was the coldest Britain had known in over 200 years. First the fog crept in. My nostrils tightened against the thick yellow damp, sour with the smoke of coal fires and diesel trains. As November wore on and the cold deepened, fog froze into hoar frost that thickened daily on the power lines until they resembled sagging ropes.

Snow began the day after Christmas. All January it snowed and froze and snowed again. Transportation systems ground to a halt. The River Thames froze over. The inside wall of our apartment kitchen, wet since November and already black-mottled with mildew, glazed over with ice. On the outsides of buildings, ice congealed around plumbing outlet pipes like candle wax dripped from lighted candles. Water pipes froze and burst. The clatter of buckets as the water truck made its rounds became a familiar sound in our Windsor neighborhood.

Windsorians walk on the frozen Thames.

A view towards Windsor Bridge photographed on 24 January 1963. Image from the Royal Windsor Website

A side benefit of the bad weather was that we got to know our neighbors. Here’s a letter I wrote to my parents:

23 January 1963

I think we must be drifting into another ice age – the weather here continues to get colder every day. All sources of fuel – coal, gas electricity, and even paraffin, are in short supply, and everyone is fighting a losing battle against frozen pipes and general seizing up.

We had our fun and games over the weekend. We were woken fairly early on Saturday morning to terrific shouting and hammering on the door. We staggered out, to find that the Hoopers were being flooded out – their kitchen was an icy pond, and water was pouring through the light fitting in the ceiling. We turned off all the taps we could find, someone somehow found a plumber, and after he, Tony and Peter [Hooper] had hacked their way through the several inches of ice outside the front gate, and even more ice on top of the valve, they managed to get the mains off. Next thing we tried to get in touch with Stan Fricker, from whose flat the water was coming – he was at work, and we had visions of him coming home to a complete flood. By the time he arrived we had swished most of the water out of the kitchen, and had got all the heaters we could find in to dry it out. So we all trooped up into Stan’s bathroom, which is directly above the Hoopers’ kitchen and, to our surprise, found very little trace of water. We bailed the solid chucks of ice out of the bath, which had been frozen up for days, and Stan and Tony got to work on the floorboards, which were suspiciously damp. They managed to raise a couple, and discovered that the break in the pipe was right underneath the bath, which had been very recently closed in and modernised with plywood, fresh paint, and what not. A brute to get at.

The next thing to do was to find a plumber to fix it – easier said than done – “Oh no, love, we couldn’t possibly let you have one till Monday.” I don’t know how many pennies we spent on phone calls over the weekend, but at fourpence a call we went through several shillings. But we still couldn’t get a plumber till Monday, and late Monday afternoon at that. So we borrowed buckets of water from a neighbor, and puddled along with little dribs of washing where necessary, keeping most of it for drinking. It was pretty messy. At least in the old days they had facilities in keeping with such conditions – but try using a modern-type lav when you have nothing but half a bucket of dirty water to flush it with. That was the first thing that Margaret [Hooper] did, with great ceremony, when the plumber finally managed to get the water on again for us on Monday evening. Our lav had to wait a few hours longer – the remaining water in it had got so iced up that it had to be very carefully thawed before anything would move. And we still can’t have a bath – the outlet pipes in the bathroom are frozen up and, according to the plumber, that will just have to wait till the thaw.

The kitchen outlet, which comes down in the same place – down the outside wall on the coldest side of the house, now shows signs of doing the same thing, which would be choice. I am shortly going to do some washing, and hope that the gallons of hot water from the tub will deter it. Still, we could always throw our slops out the window – if we could unfreeze the windows enough to open them, that is. Might as well be really primitive.

We are getting rather advanced ideas on the proper requirements of a house in this climate – they do not agree very much with the conventional buildings most people live in here. Definitely central heating, double glazing, and interior plumbing.

A cool way to help restore a forest

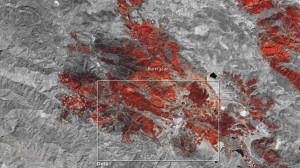

In neighboring Lake County this past summer, wildfire destroyed 76,000 acres of forest (about seven million trees) and nearly 2000 homes, businesses and other structures. Mendocino Coast Botanical Gardens has stepped up with their Lake County Giving Project. One component of the project encouraged people to purchase potted trees and other plants for their holiday decorations, then bring them back to be donated to Lake County residents rebuilding their homes.

Zoomed-in false-color shortwave infrared satellite image showing the Valley Fire burn scar near Middletown, California on September 20, 2015. Burned areas appear orange or dark red. (NASA Earth Observatory)

The other component of the Giving Project is seed balls. With advice on plant species from the USDA Resource Restoration Project and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Wild Jules is crafting seed balls of wild grasses, perennials, and annual wildflowers for habitat restoration in the fire-ravaged areas. According to the Wild Jules website, “Individual varieties of seed are proportionately mixed with red clay and compost to provide a self contained method of spreading native varieties. The ball protects the seed from birds and rodents. The seed cannot dry out or blow away. The best part is, you can cast these ‘jules’ (jewels) out on top of the soil any time of year. The seed within the clay balls will wait patiently to germinate until adequate water is applied by way of rain or irrigation.”

A Wild Jules seed ball. The balls being prepared for Lake County habitat restoration are a little more flattened so that they stay put on steep hillsides.

Tony and I were intrigued enough to stop by the Garden Store to donate a few dollars to the seed ball purchase fund.

Julie Kelly, founder of Wild Jules, says: “It’ll take many years but every bit counts. The perennials won’t bloom this year, but the annuals will. They will help feed foraging insects and birds and lift the spirits of the folks so terribly impacted.”

Good old days at the post office

In December of 1962, before there were mail codes or mechanical sorters, I worked for a week at the post office in Windsor, England, helping with the Christmas rush. I mentioned it in letters to parents:

18 Dec. 1962

…Hope this reaches you in time for Christmas – along with the other thousands of tons of mail being posted this week. I know – I have to sort the stuff. I am spending the week working in the sorting room at the post office. Very difficult job! – turning the stamps up the right way as the letters come out of the postbags. Have to work pretty hard, but it’s rather fun – very cheerful, friendly crowd – and good money.

26 Dec. 1962

…I had a very interesting week in the Post Office. Halfway through the week I was promoted to sorting, which was a bit more fun, though harder work than facing up.

Those were the days, before email, Facebook, Twitter and other social media, when the annual holiday greeting card was how one kept in touch with extended family and friends. According to Wikipedia the custom of sending greeting cards has a long history, dating back to the ancient Chinese. The postage stamp was introduced in England in 1840. Cards started being mass produced by the 1850s. From then on, mailboxes became crammed each December with penned good wishes.

Every card and letter had to be sorted by hand. Mechanical sorting, which depended on reducing the address to a machine-readable form, came in a few years after my stint at the Windsor post office: the 5-digit ZIP code was introduced in the U.S. in 1963, and England’s alphanumeric postcode system in 1966.

Communication methods have changed, and fewer greetings now go by “snail mail.” The U.S. Postal Service reports that First-Class Single Piece Mail; that is, mail bearing postage stamps, such as bill payments, personal correspondence, cards and letters, etc., declined by 47 percent in the decade 2005–2014. But that urge to reach out to those we love during the holiday season is still with us.