Posts Tagged ‘art’

The place of art

What is art, and what place has it had in my life? This was the assigned topic for the first set of high school student essays I graded in my first paying job in California. In those days, the late 1960s, California schools had enough money to hire readers to relieve teachers of the time-consuming task of grading papers. I worked primarily with Millicent Rutherford, the Humanities teacher at Lynbrook High School, in the Cupertino Union School District. Over time, we developed a warm friendship.

I was saddened to learn that Millicent died last October, at the age of 91. Her obituary notes: “She will be remembered for her glittering sense of style, her sharp wit, and her boundless energy.” A 1991 Los Angeles Times article on remembering teachers who made a difference includes an anecdote by Stephen Bennett, CEO of AIDS Project Los Angeles:

“We’d study Italian art and [Ms Rutherford] would get . . . photographs from some of the Pompeian paintings that are not typically looked at—the parts of Pompeii they won’t show you because the graphics on the wall are what Americans would consider lewd. And she’d show up in a Pompeian red dress to start the day.”

To honor Millicent’s memory, I’ve been thinking about how I might respond to her essay topic.

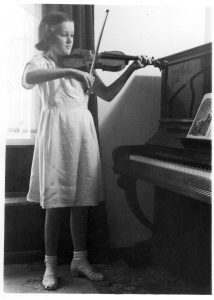

When I was the age of Millicent’s students, music was my passion. I played second violin in my town’s municipal orchestra. At my first concert, the orchestra tackled Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. It must have sounded decidedly amateurish. But the experience of being a part of that magnificent work, of sharing the language of music with my fellow musicians and with an audience, is a thrill that has always stayed with me.

Tauranga Municipal Orchestra at rehearsal in the high school assembly hall, c. 1952. I am in the front row, just to the left of the podium.

Painting too speaks a language without words. On the wall of my office is a reproduction of Georges Rouault’s “The Old King.” I saw the original fifty years ago, at the National Gallery in London. Friends I had come with moved to another room without me as I sat on a gallery bench, weeping. I still weep inside when I look at it.

Concerts, theatre, dance performances and visits to art galleries have always been a major part of my life. The written word has been my personal art form. To struggle with the lines of a poem, to convey emotional meaning through images, leads me to a personal answer to the question: “What is art?” For me, it is a way of sharing what is meaningful in our lives.

Art stuns like a hammer blow

With gold velvet drapery as backdrop, the newly acquired Rembrandt, “Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer,” stood on an easel in the foyer of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Spotlights accentuated the golden glow of the painting’s surface. As I gazed, I felt a resonance with the feelings of the person depicted, my thoughts drawn into his as if into a dizzying vortex. I was astounded that brushstrokes and pigment could have such power to move me.

I had not seen great art before, except in books of reproductions. I had devoured the collection of large format books in my high school art room, and spent hours browsing the art section of secondhand book shops when I was in college. When we left New Zealand in 1962, Tony and I had as a priority to visit art museums and see the work of artists we admired. But nothing had prepared us for being in the presence of the real thing. Upstairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art we found a whole room of Rembrandts. Dancing down a broad staircase, a whole series of bronze sculptures by Edgar Degas. We saw so many great works we discovered the phenomenon we named “mental indigestion” and wished we had more time in the city so that we could come back. We knew it would take weeks, months even, to absorb all this museum had to offer.

We visited other art museums during this stopover in New York on our way to England. Some we loved, some less so. In a letter to parents I wrote: “Sunday afternoon we went out to The Cloisters, which is right up at the northern tip of Manhattan. This is a religious museum. Parts of the remains of many old churches of Europe have been brought across and incorporated into the present structure, which keeps as closely as possible to the original styles. In a sense it is a success – some of the old fragments of stonework are very fine, and there are some very fine paintings, altar ornaments, and some magnificent tapestries – the highlight of the whole exhibition. But in spite of their attempts to reproduce chapels, all sense of reverence has been lost – the things are a curiousity for the locals to gawp at, and even sacrilegious.”

As I look back on these youthful letters and these memories, I see opinions about what matters to me already forming and clarifying. Many more experiences of the power of art would come in future years: sitting on a bench in a crowded London gallery, weeping over Georges Rouault’s “The Old King;” gazing in awe at the rose window in Chartres Cathedral; feeling the silence of the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Always, enriching these experiences, the memory of that stunning awakening in New York.

Word Art

I spent this morning thinking about the intersection of writing and art — how we can be moved by a piece of art that involves words, even when the writing is undecipherable. Or when you are ignorant of the language, as I was recently in Istanbul, where I was captivated by the Arabic script that decorated walls of mosques and palaces.

Last night was the opening celebration in Mendocino for the show “Boundless: Art of Letter, Word and Book,” which curator Janet Self describes as a “hands-on conversation about art, language, books, and engagement in the modern age.” I have several pieces in the show: a poem collaged onto a cast paper fish, the poetry box from my vegetable garden, a handmade book that employs a complex flower-fold structure (suggested by Alisa Golden in “Making Handmade Books”), plus some broadsides and tiny chapbooks.

As I looked around the room, I saw uses of the written word that sparkled with creativity. Janet has posted some pictures on her Flockworks blog site. Among my favorites were “House of Cards,” a walk-in house shape whose walls were linked postcards from all over the world, sent years ago to members of the same family, and inherited by the house-maker. I chatted with Harry Van Ornum, a calligraphy student who, having filled his practice paper with lyrics by a favorite singer, turned the paper sideways and continued, making of the words an abstract form. Janet Self, faced with a huge collection of her father’s Reader’s Digest Condensed Books that no thrift store would take, repurposed the pages into large, flowing geometric sculptures.

My favorite encounter was with a young man who stood entranced in front of a calligraphic painting by the late Jim Bertram, one of the artists who helped found the Mendocino Art Center in the 1960s. It was part of a collection being sold as a fund-raiser for Flockworks, the tiny nonprofit that creates such community art projects as the “Boundless” show.

“Excuse me,” he said. “Can you tell me if that calligraphy is in some language?”

Having met and written about Jim Bertram not long before he died, I was able to tell the young man that no, the beautiful shapes were not words. I told him about the quote I found while researching this artist: Line expresses the inner thought. It is a narrative of what we really want to tell each other but somehow can’t seem to verbalize.

“Now I really want that painting,” the young man responded. “I don’t have any money. But next payday, I’m coming back to buy it.”

Transience

The print that hangs on my study wall is old now, as I am. When I look at it I remember seeing the original painting, Georges Rouault’s “The Old King,” in London in the early 1960s. It was on loan from the Carnegie Museum of Art, part of some big exhibition. The Tate or the National Gallery, I don’t remember which. A crowd of viewers. The friends I was with moved on to other rooms in the gallery. I stood rooted in front of the picture, tears streaming down my face. Read the rest of this entry »