Posts Tagged ‘nature’

In Praise of Parks

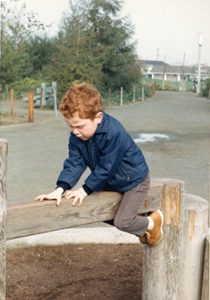

Having spent all their little lives in a place where parks had prim Keep Off The Grass signs and irate men in bowler hats with sticks enforced The Rules, my children were enchanted to discover the parks and playgrounds of their new home.

In the 1967, when we arrived in California from England, California State Parks was going through a huge expansion. Appropriations from the General Fund and a 1964 recreation bond provided well over a hundred million dollars for land acquisition and development. The government budget analysis for 1967 comments:

In the immediate future, the most pressing need of the state park system will be to provide funds for access and minimum development to enable the public to use lands now owned or currently being acquired. The existing state park system has a potential for development of about four times that of existing facilities.

With an expanding population, local governments in the Santa Clara Valley were also opening new parks and playgrounds as rapidly as they could. It was a fine time to be kids. They had their choice of playgrounds within easy driving distance: the one with the great swings, or the one with the good bars to climb on?

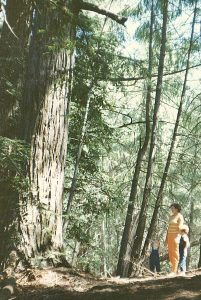

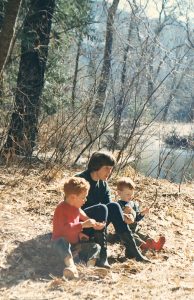

Cooking out at a forest park was one of our favorite activities. We bought a cheap little hibachi, loaded up a picnic and were off to explore.

At weekends, if the weather was hot in the valley, we might go over the Santa Cruz Mountains to the beach, remembering to take warm jackets since the fog was likely to roll in. Again choices, choices: Pescadero State Beach, or San Gregorio, or Half Moon Bay, Natural Bridges, Seacliff, Manresa…? Well before the California Coastal Act of 1976 declared that the permanent protection of the state’s natural and scenic resources is a paramount concern to present and future residents of the state and nation and that it is necessary to protect the ecological balance of the coastal zone and prevent its deterioration and destruction, the beach parks in our part of the state were already a beloved treasure.

Looking back, I recognize how innocent we were about land use politics, environmental pollution issues, climate change. Now more than ever, those parks and beaches, and the creatures living in them, need our support.

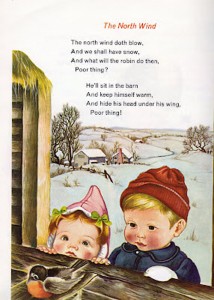

Robin redbreast on a fence

I still ponder why it meant so much, that Christmas morning in England in the 1960s, that a robin sat on the back fence. The field behind the fence was white, the fence wires thick with hoar frost, and the little red-breasted bird made the scene perfect. Finally, I told myself, a ‘real’ Christmas.

I have tried for many years to clarify my feelings about the disconnect between the traditional trappings of the season and my experience of growing up in New Zealand, where the seasons are reversed. My childhood Christmas memories are of summer: the tree laden with oranges in my grandmother’s garden where we hung our presents and picnicked on the lawn; the scent of magnolia blossom outside the church on Christmas Eve.

Also the Christmas cards with their images of snow (which I’d never experienced) and yes, the English robin. I knew about robin redbreast from the old nursery rhyme, but until that Christmas I hadn’t seen one.

Now on the coast of Northern California, I have a different understanding of how to celebrate the winter season. Our multicultural society recognizes many winter festival stories and traditions: the birth of Jesus in a stable, the menorah candles of Hannukah, the Swedish light-bringer St. Lucia, the gift-bringer St. Nicholas (known also as Santa Claus), and many others. The celebration that holds the deepest meaning for me now is Winter Solstice, the return of the light. From summer to winter, I note where on the horizon the sun sets, and how the darkness grows. Even as clouds gather, the place where sun disappears into ocean fogbank moves steadily to the south. When the prevailing westerly wind shifts to the southeast, I know to expect the winter rains. Sometimes a shower or two, sometimes, such as this past week, a prolonged deluge that floods rivers, downs power lines, and closes roads.

Meanwhile, the earliest spring flowers are breaking bud, and over-wintering birds gather hungrily at my feeder: Steller’s jay, spotted towhee, hermit thrush, acorn woodpecker, hordes of white-crowned sparrows. I love them dearly. I am happy that I have learned to understand the connection between the flow of seasons and human efforts to explain them with stories and festivals. And I still have a place in my heart for the memory of that cheery robin redbreast who brightened an English winter.

The Language of Plants

Have you ever wondered whether trees talk to each other about what’s going on in the forest? Can they show compassion or motherly love? Do they team up to ward off an attack?

Recent research has shown that plants communicate using an electrochemical “language.” Taking a break from exploring my old black filing cabinet, I’d like to share a poem about this discovery. It’s from my new collection, Earthward, available from Finishing Line Press.

The Language of Plants

We who move about are at a loss.

We do not know what words to use

for speech that has no metaphor

in the human tongue.

We have ways to speak of learning,

words for memory, decision-making words.

We speak of synapses of neurons in our brains,

name the organs that receive our senses—

ears, eyes and noses, taste buds, fingertips—

words all based on human forms.

The standing-still ones

message their pheromones into the air:

Aphid invasion. Deploy toxin defenses.

Send for the predator wasp to counter-attack.

Roots zing with electrochemical charge

as through their internet—

a mycorrhizal tangle of yellow threads—

they share resources with their kin,

and even with neighbors of other ilk:

Fir borrows summer sugar from birch,

pays it back in the time of barren twigs.

We need new definitions to embrace

the beings who feed on light

not in some alien galaxy

but close at hand:

Does intelligence mean to have a brain

or problem-solve?

New ways of standing in a bean patch

or a forest grove

in awe and wild surmise at all

this human brain can not yet comprehend.

Doing by Not Doing

I thought I was retired from running the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference. But life happens, and so do medical crises. So I’m back as Acting Executive Director, scrambling to pick up the threads of all the detailed tasks that make up a successful conference and continue weaving them into a sweetly patterned braid.

I’ve done it before, several years of befores. My challenge is to keep calm, level-headed, unstressed. I know that to do my job well, I need to take time to do nothing.

This morning Tony and I took one of our favorite walks: from Laguna Point at MacKerricher State Park south along the cliff edge to Virgin Creek Beach, then footprints on smooth wet sand to where the water of Virgin Creek ripples and glitters as it crosses the beach to the sea. There we leave the beach and, picking up our pace, take the weather-beaten old haul road back to the Laguna Point parking lot.

This afternoon as I sit on my front porch, a white-crowned sparrow is singing from a nearby bush. Hummingbirds are working over the purple Mexican sage and yellow sticky monkey flower in front of me. I hear chirps from newly hatched Stellar’s jay chicks as a parent flies in to their nest in the wisteria vine. A violet-green swallow has come and gone from the porch corner cavity where they’ve sometimes nested. Two stems of dry grass dangle from the cavity. Not a good place this year. I warn them in my mind to beware the predatory jays.

Inspired by a talk a year or two back by Lewis Richmond, author of Aging as a Spiritual Practice, I am learning to meditate. It’s hard to push away the clutter of to-do lists, but I think I am making progress.

The mission of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference is to offer a place where writers find encouragement, expertise and inspiration. As executive director, my encouragement comes from the support and expertise of a wonderful team of volunteers, some of whom have been helping to run the conference for nearly all of its twenty-five years. My inspiration comes from the beauty of the pattern I braid from all these threads of tasks in my hand, its colors imbued with the memory of sea and headland, forest and garden, its thread tension even, unmarred by crises.

For the sake of all the writers who leave Mendocino Coast Writers Conference inspired by the supportive atmosphere the conference team creates, I can do this.

Encounters with Newts

Now that our rains have finally started, the newts have come out of hiding. Last week I spent a couple of days at Green Gulch Farm, a Zen Buddhist retreat center and organic vegetable farm near San Francisco. California Newts were all over the paths. Their brown skin smooth, their underbellies a brilliant golden yellow, they were marching to the streams where they breed.

This morning we had to step around another California Newt on a path at the Mendocino Coast Botanical Gardens, a little one in its rough-skinned terrestrial phase. It was reluctant to move, since it was busy consuming a large earthworm; the last half-inch of the worm still hung from its mouth.

These encounters reminded me of visiting Montgomery Woods some years ago, when their close relatives the Red-bellied Newts were everywhere. I became fascinated with the story of their breeding migrations and wrote this poem, which was published in my 2007 chapbook, Quickening.

Red-Bellied Newt (Taricha rivularis)

What stirs, with the rain, that urge to return?

Some years she ignores the tingle in her nose,

the scent of that particular section of stream

where under a stone she hatched into a nymph,

then played for a year in the rippling water

before crawling transformed up the bank.

Summers she hides. Home is a secret hollow

under gnarled redwood roots in the ancient grove.

Some winters too. But once in a while, when the rains begin,

she emerges to make the journey to her breeding place.

Purposeful, she crawls, the red of her feet and belly

bright against the redwood duff,

navigating by smell to the rocky stream a mile away,

not home exactly, but the place she came from,

that pulls her back as it pulled her mother back.

Here she will mate, immersed in the water that gave her life,

deposit the fruits of her procreation under a stone,

then wander off to find good forage for the summer.

For thousands of years, as the giants grew overhead,

her kind have made this journey, secure in their faith

that the stream will still flow clear and fast over rocks.

They raise a question: what pulls us humans,

and to what deep places, and what is it we deposit,

like fertile newt eggs on the undersides of stones?

Citizen/Science

A king tide this morning, and we’d heard that it would be useful for people to document how high the water came, so that we’d have some idea what to expect as climate change brings rises in sea level. An excellent excuse to amble down to Big River Beach in Mendocino with my new camera and practice getting my horizons horizontal.

We’ve had no major rainstorms yet this winter to wash out the sandbar that builds up at the mouth of the river. From a vantage point on the cliff, we watched the tide creep over the bar, then took the old steps down to the beach to check on the tide height at the bridge. Yes, the water was high, too high to walk on sand and touch the bridge pier, as we can usually do.

Strolling back along the tide line, we were enjoying the peace and quiet beauty of the scene when I noticed something that set my teeth on edge: a plastic dog poop bag discarded by a driftwood log. I’ve seen such offerings frequently around this region: beside a signpost, on the edge of a trail. I want to shake the humans who leave them, who are so unclear on the concept of citizenship they have no thought for the environmental mess they are causing. It’s no wonder the sea level is rising.

Texts

Searoad, a story collection by Ursula K. LeGuin, has a permanent place on my bedside table. It’s there because every now and then I need to reread a certain story. A very short story, less than three pages, it is titled “Texts,” and tells of an older woman who, bombarded by messages and calls to action, retreats to the coastal Oregon village of Klatsand for a month-long winter break. As she walks on the deserted beach, she notices that the waves have left messages in the lines of foam, messages she can almost decipher. The laciness of the foam leads her to speculate that crochet work and lace might also be legible. In a handmade lace collar she reads a message that seems directed to her: “my soul must go, my soul must go … sister, sister, light the light.” There the story ends, with the woman not knowing “what she was to do, or how she was to do it.”

I think of this oddly moving little story every time I walk on Ten Mile Beach, as I did last Sunday. The receding waves left undulating lines of bubbles, iridescent in the hazy sunlight, that popped to form patterns of foam. Scattered across the beach were strands of bull kelp, dried into coils and loops that lay like a cursive script on the sand.

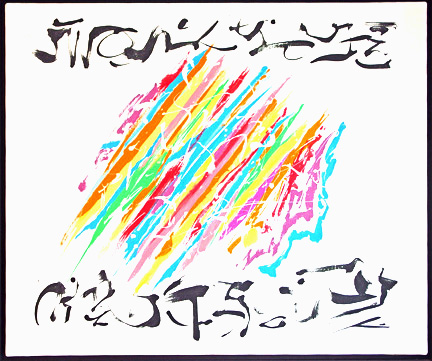

Yesterday, when the wind was brisk and the sea streaked with white caps, I remembered an interview I did for the Mendocino Art Center magazine. It was part of a series I wrote on artists who helped found the art center in the 1960s. By the time I met Jim Bertram in the early 2000s, he was senile and nonverbal, so I had to rely on material in the art center archives for information about his background and artistic vision. Nevertheless, Jim and I spent a wonderful afternoon together. I think a poem I wrote at the time sums it up:

MESSAGES

For JB

“Line expresses the inner thought. It is a narrative of what we really want to tell each other but somehow can’t seem to verbalize.”

– Jim Bertram

These bright spring days, when the wind

scribbles its white calligraphy

on a wash of aquamarine,

I think of the artist in his studio

upstairs of a weathered storefront

overlooking Mendocino Bay.

Sheet after curling sheet he showed me, canvas

after canvas, covered with calligraphic forms

that could have been words, but were not.

In our shared silence I understood his drift:

how sometimes what matters most is inarticulate:

like the line of spray from a lifting wave,

the hand of an old man painting messages of love.

On my way downstairs from Jim’s studio, I fell in love with one of his paintings, which now has a place of honor in my house. I smile when I read its message.

Juncos

A flock of twenty to thirty Oregon Juncos around the house yesterday, the most I’ve ever seen together. Such handsome, busy little birds. It gives me pleasure to know that the habitat we’ve created provides sustenance.

Prison Guard-ening

On top of the roadbank, I am fastening circles of heavy wire mesh around young Leyland Cypresses. A passing neighbor calls a greeting. “Prison guard-ening?” she asks.

“Yeah,” I reply with a shrug of despair. She too is a gardener. She understands.

Ever since my husband and I built this house at the edge of the forest, we have tried to live in respectful community with the creatures who were here before us. Jackrabbits, foxes and bobcats use our ground-level front porch as a convenient highway. My vegetable garden is fenced off, but the resident blacktailed deer amble through the rest of the garden wherever they please. They even help by pulling juicy weeds from among the deer-resistant perennials and by keeping down the path to the compost bins more efficiently than a lawn-mower.

The only problem I have is with the bucks, who scrape off the velvet covering their antlers by rubbing them against young trees and shrubs. Already some of the cypresses show the telltale signs: a snapped-off branch or frond turning brown, a length of the trunk rubbed raw. It’s a mating signal, I understand, with several facets: the visual sign left by the buck’s rubbing, chemical signals from glands on the buck’s face, and the sound of the buck thrashing branches of the tree on which it is rubbing. I once watched a large buck do battle with a stiff and spiny Ceonothus bush by the driveway. Again and again he attacked, as if determined to demolish it. Here on this roadbank I have lost a Pacific Wax Myrtle and a couple of Shore Pines to such opponents. The Cypresses are a replacement, to help fill in a windbreak against our fierce nor’westers. I can’t afford to lose them too.

The prison cages are unsightly, and don’t fit with the natural landscape I’d like to have. But Cypresses grow quickly; soon their foliage will hide the wire. Sometimes compromises must be made.

Quail Update

After I disturbed a quail on her nest in the walled garden in back of my house, I kept the gate closed for three weeks, which I learned was the typical incubation period for quail chicks. This morning I crept in, anxious about what I might find. I eased back a branch of thimbleberry, and cautiously lifted the thatch of dry blue-eyed grass. I glimpsed the rounded shape of an egg. Oh no, had the nest been abandoned? I looked closer. There were empty eggshells aplenty, neatly halved and stacked together in the grass-lined bowl of the nest. Eight or nine chicks have hatched and headed out into the big world. I’ve not yet seen them, though I’ve heard parental burblings from the bush-covered hill above the wall. Bon aventure, little ones.

I also had a chance to study the eggshells more closely, and realize I was mistaken in their color. They have a bluish cast, but the color is more of a creamy tan, speckled with brown blotches.