Posts Tagged ‘poetry’

Sharing the joy of language

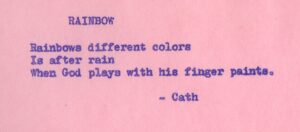

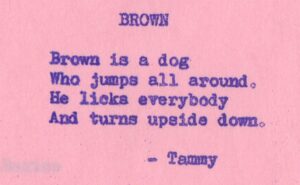

In my old black filing cabinet I find a treasure: a few stapled sheets of pink copy paper printed with the unmistakable purple ink of a ditto machine. It is the output of my first poetry teaching gig. I explain in a letter to my parents.

In my old black filing cabinet I find a treasure: a few stapled sheets of pink copy paper printed with the unmistakable purple ink of a ditto machine. It is the output of my first poetry teaching gig. I explain in a letter to my parents.

March 1, 1971

I am starting on Friday teaching one hour a week at [my son’s] school. This is what they call a scramble program, where 1st, 2nd and 3rd graders (6-9 yr-olds) are all mixed together to take activities of their own choice, from a list that includes ceramics, folk-dancing, tennis, guitar playing, cookery, woodwork, arts & crafts, etc. The teachers and mothers involved get to teach whatever they are interested in. I am taking a group who are interested in writing poetry. It should be fun, but requires a lot of preparation.

As a university student in New Zealand I had chosen not to make teaching my profession. I’ve not regretted this decision. But over the years I have enjoyed the challenge of teaching short-term writing programs, though even this first one had its moments.

As a university student in New Zealand I had chosen not to make teaching my profession. I’ve not regretted this decision. But over the years I have enjoyed the challenge of teaching short-term writing programs, though even this first one had its moments.

March 29, 1971

My poetry class is coming along quite well, though conditions were a bit poor last week – it was raining, & all the frustrated outdoor games kids crowded into the library too, & my poor kids couldn’t get into the mood.

At the end of the program I would have made enough copies of the pink sheets for all the children in my group to take home. I still remember the frustration of making ditto masters, using a manual typewriter with the ribbon removed. Any mistake and you had to start over. I still remember the smell of the alcohol solvent that permeated the printed pages. I also remember the children’s joy in the power of language.

Today I’d like to give a shout-out to California Poets in the Schools, a program that not only places poet-teachers in classrooms, but also provides training and resources to help them in their work of “empower[ing] students of all ages throughout California to express their creativity, imagination, and intellectual curiosity through writing, performing and publishing their own poetry.” And I’m in awe of the technologies that support a quality of publication way beyond my pathetic purple dittoes.

Going Dark

In 1966, my friend Diana Neutze developed multiple sclerosis (MS). She was not yet thirty years old.

I first met Diana about ten years before this, when we shared English Lit. classes as freshmen at Canterbury University in Christchurch, New Zealand. During school breaks we worked as kitchen hands at the same remote fishing camp. I was part of her wedding, and she of mine. We lived next-door to each other as young marrieds, and shared survival tips as penniless expatriate mothers of small children in London. Even after I moved to California and she returned to New Zealand, we stayed in touch as best we could.

For decades Diana’s illness came and went. She learned to live with it, devising ingenious stratagems for making sure she stayed mobile and independent. Whenever possible, she refused medications. All she had left, she said, was her mind, and her ability to find joy in music and the beauty of her garden. Painkillers took that clarity of mind from her, and this she could not allow. Right up until the end she was writing and publishing poetry. (I reviewed a recent book in these pages) I introduced her, via email, to a quadriplegic friend who got her started with voice recognition software. When she could no longer edit using one finger on a keyboard, or see to read, she dictated edits to a carer.

Diana and I traded poems and, as her body slowly but inexorably closed down, thoughts about death. She was in my mind when Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino invited local poets to respond to Wendell Berry’s poem “Going Dark” at a 2012 Winter Solstice event. I sent the poem to Diana, and included it in my new chapbook, Earthward. When I spoke to Diana via Skype in April 2013, three days before she died, she accepted my promise to dedicate Earthward, to her memory. At her request, my poem, “Going Dark,” was read at her funeral. Here it is:

Going Dark

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

— Wendell Berry

My friend’s body is a brown leaf,

shriveled and curled inward.

Pain is a constant, yet

the fierce flame of her will

refuses surrender.

It’s not death’s darkness she resists

but the loss of a self transfixed

by what is beautiful:

a Bach air, the light

through her walnut tree.

This dark she speaks of

has no scent of earth,

no draft from unseen wings,

no sudden rustle in the undergrowth.

What can I say to her, and to myself,

this season of gathering in

our lives against the rainy dark,

against the ancient fear

that light will not return?

Just this: a dry leaf

fallen to ground disintegrates,

becomes the food that nourishes

all that sweetly blooms and sings.

My chapbook Earthward is available from Finishing Line Press. The direct link is: https://finishinglinepress.com/product_info.php?cPath=4&products_id=2129

Some of Diana Neutze’s poems can be read on her blog site, Living With Multiple Sclerosis.

My new poetry collection

I am excited to announce that Finishing Line Press is now taking pre-publication orders for my new poetry collection, Earthward. It can be ordered now and will be printed and shipped in October. You can order online from the publisher at https://finishinglinepress.com/product_info.php?cPath=4&products_id=2129

The cost is $14 plus $2.99 shipping. The publisher bases the size of the print run on how many pre-publication orders they receive, so I hope you’ll consider adding to my tally. Please feel free to suggest this book to others you think might be interested too.

The poems in Earthward explore the cyclical patterns of life. Here is a sample poem:

Osprey With Fish

Undercarriage of leg and talon

joins two bodies similar

in sleekness,

twinned

as life and death conjoin

in a continuum

of nourishment.

Huge wings slow over forest,

a fading cry.

I’ve been honored to receive reviews from poets I admire:

With a naturalist’s eye for the precise and sensuous image and a writer’s care for the precise and sensuous word, Maureen Eppstein plants our human griefs into this book, roots them, and invites them to quicken into new life.

—Jane Hirshfield, author of Come, Thief

What captivates me about Earthward is the way Maureen Eppstein transforms ordinary landscapes into miraculous acts of affirmation. Turning compost becomes an opportunity to ponder death and resurrection, braiding garlic reminds us of the “pleasure taken in braiding the hair of the beloved”. This is poetry of quiet lyrical depth, that reconnects us with land and spirit. Earthward invites us to stand deeply rooted in each moment, “in awe and wild surmise at all this human brain can not yet comprehend.”

—Devreaux Baker, author of Red Willow People

In Earthward, Maureen Eppstein unites what would break us with what will bring us back to life. The wild ones, like us, must eat, and so kill. Lost sisters are mourned by proxy. Some things we love are transplanted and transplanted again, surviving and sometimes thriving. The tenacity Eppstein describes is the foundation of our lives. There are those who say that to write about the extraordinary one must look lovingly at the ordinary. Eppstein knows where, and how, to look.

—Camille T. Dungy, author of Smith Blue

Here’s a brief bio:

Maureen Eppstein is the author of two previous poetry collection: Rogue Wave at Glass Beach (2009) and Quickening (2007), both published by March Street Press. Quickening was also first runner-up in the 2007 Finishing Line Press/ New Women’s Voices competition. She has been a finalist in several other book contests. Her poetry has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including Poecology, Calyx, Basalt, Written River, Sand Hill Review, and Aesthetica 2014, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Crossing the boundary between the arts and the sciences, her poems have been included in a textbook on computer graphics and geometric modeling and used in a university-level geology course.

A Little House for Poetry

The idea came from an article in the Sept.-Oct. 2013 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine about a project to erect small installations, called poetry boxes, in public places. Their purpose, according to the artist, is to “connect people to landscape by combining poetry, visual art, and nature observation.”

The idea came from an article in the Sept.-Oct. 2013 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine about a project to erect small installations, called poetry boxes, in public places. Their purpose, according to the artist, is to “connect people to landscape by combining poetry, visual art, and nature observation.”

I decided to design a poetry box for myself. A simple little house, with just a touch of decoration: a carved spiral to symbolize the continuity of life, and a line of chevrons to signify water. I have no skill at woodwork, but my husband Tony does, and he readily agreed to take my plan and build it.

Here it is, mounted on the 6” x 6” gatepost of my fenced vegetable garden. The laminated text is thumbtacked to the back of the box, so that I can change it whenever I want to. For its debut, I placed an empty seed packet on the floor of the house and pinned up a few lines from my poem “Winter Greens,” which is published in my collection Rogue Wave at Glass Beach.

This is the gesture of hope:

to remember the taste of fresh-cut salad greens

and act on it.

This is the act of reconciliation:

muscle rhythm of shovel and wheelbarrow,

load upon load to fill the planting box.

This is the sound of faith:

a rake tamping down soil over new plantings—

snap peas, bok choi, lettuces—

tines on the diagonal, first one direction

then crisscrossed down the line.

Canticle for the Winter Solstice

I plan to read this poem at tonight’s Solstice event at Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino. Obviously it was written in a year other than 2013. We’ve had no rain all month, and none in the extended forecast, so face the likelihood of a drought year. I think of this piece as a kind of prayer.

Canticle for the Winter Solstice

I honor the rain that plummets from a leaden sky

on this day when the dying sun returns to life.

I honor the wet earth where fungi lift

the smells and secrets of their darkness

into forms potent with wildness

and fallen leaves grow slimy with decay.

I honor the sudden green suffusing

the face of the sun-scorched hill,

like the blush of knowledge in a woman’s face

after her first coupling.

I honor the flame of candle and hearth

that draws to itself the breaths

of all whose lives have sometime crossed,

mingles and transmutes them into warmth

and sends them out into the rain

where they caress the tender growing tips of trees.

Rain

This last month of our annual dry season, as grasses turn dusty brown and the trees droop, a phrase from a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem has been running through my head: “Send my roots rain.” This week the first good downpour broke the drought. I found and reread Hopkins’s poem, and recognized in it the cry of every writer who, like myself, goes through a dry spell and pleads for the rain of words and ideas.

Hopkins’s sonnet begins as a Job-like argument with God. He is angry that “sinners’ ways prosper” while he, a Jesuit priest who spends his life “upon thy cause,” sees his every endeavor end in disappointment.

The tone shifts in the second part of the sonnet. Hopkins points out the exuberant natural world:

See, banks and brakes

Now, leavèd how thick! lacèd they are again

With fretty chervil, look, and fresh wind shakes

Them; birds build …

He compares these images with his own struggles. He does not build, he says,

but strain,

Time’s eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes.

Hopkins sold himself short, of course. His poems continue to waken in the minds of later generations. But that sense of self-doubt is one all writers share. Whatever our spiritual beliefs, we can join in the prayer of Hopkins’s closing line:

Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.

You can read this sonnet, and link to other poems by Hopkins, at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/173669

A Lifetime of Friendship

“I have not written these poems, nor even read them; this is a spoken book,” declares my friend Diana Neutze on the back cover of her latest collection, AGAINST ALL ODDS. The title refers not just to her illness—she has battled Multiple Sclerosis for well over forty years—but to the difficulties inherent in transforming poems from her mind to the printed page. As MS closed down her body, she progressed from longhand, to one finger on the computer, to voice recognition. “But now I dictate to Gabrielle, my editing carer. Even the editing has been done by voice, backwards and forwards in the air.”

I was privileged to receive a copy of this handsome limited edition. Written over the past three years, the poems chronicle the poet’s recognition that her death is imminent and her determination to live each remaining day in the beauty of the moment. The poems are rich with images such as: …a tangle of branches/ peremptory against a crystal sky. She asks:

If I died tomorrow, what would

happen to the poems in my head?

Christchurch, New Zealand, where Diana lives, has suffered a series of devastating earthquakes and aftershocks that figure in many of the poems. In “Elsewhere” she writes:

…the earth where I thought

to lay my final bones

is writhing like a wounded snake.

The earthquake draws her mind outward to share a communal grief:

I mourn for the lost, the mained, the dead.

I mourn for our grieving city.

The experience of working with composer Anthony Ritchie on a song sycle of her poems draws her to a new awareness of the importance of people in her life. The final poem in the book reworks “Goodbye,” the final poem in the song cycle. Keeping the opening lines: If this day were to be/ my last …, she traces the trajectory of her preparations for death, from spiritual and inward-looking to a recognition of a fear in which …I relegated/ my friends to the outer suburbs. The poem ends:

If tonight were to be my very last,

I would be desolate

at leaving behind

a lifetime of friends.

I have been friends with Diana since our freshman year at the University of Canterbury, fifty-four years ago, where we met in English Literature class. During school breaks we worked as kitchen hands at the same remote fishing camp. We lived next-door to each other as young marrieds, and shared survival tips as penniless expatriate parents of small children in London. Over the years and across the globe we have stayed in touch, supporting each other as best we could in times of grief, commenting on each other’s poems, occasionally visiting. I honor this lifetime of friendship as I read AGAINST ALL ODDS.

Words and Music from an Inner Garden

For more than forty years, my friend Diana Neutze has endured the relentless thefts of multiple sclerosis and grief for a son lost too young. Throughout that time, she has continued to write powerful and moving poems. Recently, her body closing down, she commissioned the New Zealand composer Anthony Ritchie to set some of her poems to music. The cycle of seven songs, “Thoughts from an Inner Garden” premiered April 2011 in a performance at Diana’s house in Christchurch, New Zealand. Diana recently sent me a CD of that performance. I’ve been playing it over and over, overwhelmed by the beauty and intensity of the work.

From Diana Neutze’s published collections, A ROUTINE DAY and UNWINDING THE LABYRINTH, Ritchie selected poems that express the poignancy of the poet’s sense of connection with the tangled garden that surrounds her house, a garden that has become her world. Transcending the nightmare of her chronic illness, she finds meaning in the details of the natural world: the play of light and shadow, the song of a bird.

The cycle opens in a minor key, an ancient, timeless sound that describes a day of wet greyness without wind when the garden is holding its breath. In “Bridal,” the second song, the poet, showered by autumn gold, imagines the roses and smoke bush as witnesses to a marriage between herself and the garden. The mood changes in “Chronic,” where Ritchie’s urgent rhythm reflects the tick-tocking of illness/ relentlessly. “And the Birds Sing” is a meditation on the cycles of life and death. “A Scent of Water” offers a fragile hope in the face of grief: a frosting of growth/ a shivering of buds in the morning light. The rhythms of an old folk dance come to mind in “Meaning.” A moment in late afternoon, a blackbird singing in a weeping elm, and the day is flooded with meaning. The cycle closes with “Goodbye.” The poet recalls the garden images she will die loving. The theme of a Bach partita enters the music as she describes its architectural splendour … arch after musical arch soaring upwards.

A Long Tradition

Thirty-five years ago, a bunch of hippies in Mendocino started a tradition of getting together to read their poems. Many of the original group were at the Hill House last Sunday, to reminisce about the old days and to read their work at the 35h Anniversary Mendocino Spring Poetry Celebration. Produced by Gordon Black and hosted by Sharon Doubiago and Dan Roberts, the event drew 46 poets, of whom I was privileged to be one. I felt I was part of history.

Tongue of War

The book arrived in the mail, unexpected. Return address BkMk Press. Oh yes, I remembered, one of those poetry manuscript competitions I entered ages ago, where they send all contestants a copy of the winning book. I opened it to skim, and was immediately reading it cover to cover. Tony Barnstone’s Tongue of War: from Pearl Harbor to Nagasaki, is the most powerful anti-war testament I have ever read. I’d like to quote B.H. Fairchild, who awarded this book the John Ciardi Prize:

“…It is written in forms, especially the sonnet, and of course the meter of those forms, the pulse of human feeling unable to name itself… The diction and syntax are often blunt with the exhaustion and terror of human voices—American and Japanese, soldiers and civilians—struggling to articulate the unspeakable, to make visible that to which we have learned to blind ourselves. …I cannot help but think that having read it, an American President who has himself been privileged to avoid the horrors of the battlefield might be less inclined to send young men and women off to face them.”