Posts Tagged ‘Steve Shirley’

Fingernails on glass

The visiting baby, almost two years old, sat alone and silent by the ribbed glass door of our row house in Egham, on the outskirts of London. He paid no attention to our chatty, energetic infant of the same age, nor even to his parents. Instead, he ran his tiny fingers obsessively over the ribs of the glass. Watching him as I fixed tea for our guests, I was uneasy.

A letter to my parents dated 20 April 1965 says nothing of this unease. Instead:

We had visitors on Sunday – Steve & Derek Shirley & their little Giles, who is the same age as David. We hadn’t seen them for quite a while, & had a very pleasant day.

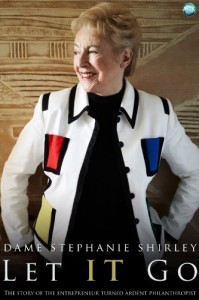

That was the last time we saw the Shirleys. Recently I have been reading Dame Stephanie (Steve) Shirley’s memoir Let IT Go, to try to understand what happened to our year-long friendship. The answer is devastating.

In early 1964 I had interviewed Steve by phone for an article that ran in the Guardian about women programmers and her new business Freelance Programmers. A few months later I gushed to parents:

30 April 1964

A couple of weeks ago we went to visit a very pleasant couple – the woman I interviewed (over the telephone) for my article on computer programmers. She has a baby the same age as David, and also works at home making up programmes – that is, the detailed instructions to be fed into a computer to do a required job. Anyway, we liked each other very much even over the phone, and she invited us to a meal to meet properly. They have a marvellous little stone cottage up in the Chilterns, right out in the country, with apple trees and daffodils, low oak beams, a huge log fire, and a grand piano squeezed into the front parlour. It sounds like a setting from a romantic novel, and that was the feeling even when we were there, that everything matched so well that it couldn’t be quite real. And a remarkable affinity too, between us as people. A bond to start with of course — it was the interest of her story that got me a place in the Guardian, and she credits me with the terrific boost to her business – she now has 20 other home-bound women working for her, and is forming herself into a limited company, and with giving her the confidence to get started. Then Derek is also a physicist [like Tony], reserved, very musical, and Steve and I found that our feelings and ideas agreed on all sorts of points.

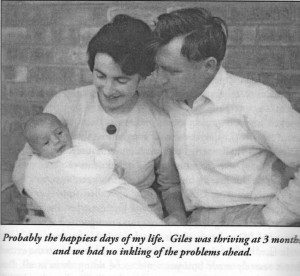

At that time Giles and our David were eleven months old. Steve writes in her memoir:

The catastrophe had crept up on us. It must have been in early 1964—when he was about eight months old—that we first began to worry, on and off, that perhaps Giles was a bit slow in his development: not physically, but in his behaviour. He was slow to crawl, slow to walk, slow to talk; he seemed almost reluctant to engage with the world around him. These concerns took time to crystallise—as such concerns generally do—and the first time I went to a doctor about them I couldn’t even admit to myself what was worrying me. …

My letters for the rest of 1964 are full of references to our new friends: visits back and forth, parties, conversations. In June I wrote: We liked them even more, if possible … isn’t it strange how people sometimes just click.

Meanwhile, Steve writes:

By the end of that year, however, there was no avoiding the observation that Giles was losing skills he had already learnt. … [He] had never become chatty. And now he fell silent. …

Months of desperate anxiety followed, in which there seemed to be little that we could do except fret. …

My lovely placid baby became a wild and unmanageable toddler who screamed all the time and appeared not to understand (or even to wish to understand) anything that was said to him…

By mid-1965 Giles had taken up weekly residence at The Park [the children’s diagnostic psychiatric hospital in Oxford] while the doctors there tried to work out what was wrong. Nothing I can write can capture the enormity of the sorrow that that short sentence now brings flooding back to me. …

Finally, in mid-1966, the specialists overseeing Giles’s case [at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children] delivered the devastating but unarguable verdict: our son was profoundly autistic, and would never be able to lead a normal life.

I understand now that our friendship with the Shirleys could not survive. Being with us would have been painful for them. There was too much unspoken, too much contrast between their child and ours. For a short time, we loved them. Even now, a sadness returns.

Postscript

Derek and Steve spent the rest of Giles’s short life seeking appropriate and supportive care for him. (He died at age 35.) Steve’s business flourished. She has poured her considerable wealth into philanthropy, primarily to support “projects with strategic impact in the field of autism spectrum disorders.”

Dame Stephanie Shirley: Let IT Go, Andrews UK Ltd., 2012

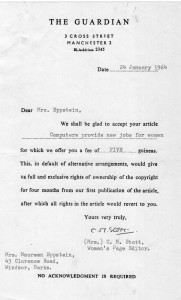

When programming was a women’s job

Back in the day when computer programming as a profession was so new it lacked a gender bias and could well have become a female specialty, I wrote an article about a woman programmer which helped launch a successful freelance business staffed almost entirely by stay-at-home mothers. For me too, it was a big breakthrough: the story was published by the Guardian newspaper on 31 Jan. 1964 under the headline “Computers provide new jobs for women.”

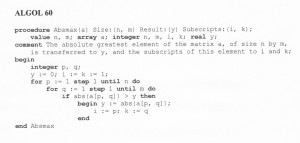

I first met Stephanie (Steve) Shirley in 1963, when our same-age babies were tiny. We had a pleasant chat about what intellectually stimulating work programming was. Frustrated with the sexism that prevailed in the world of employment, Steve had left her job with Computer Developments, Ltd., to start her own company, Freelance Programmers. Her workload was growing as new clients learned of her services, and she was starting to reach out to other former programmers for help.

In a letter to parents a week after the article was published, I wrote:

… My article was published in the Guardian, and since then I have had a flood of letters. Mainly for forwarding to the woman mentioned in it, a computer programmer, retired with a baby the same age as ours, who is trying to get other women like herself to join her in working on a free lance basis.

Less than a year after my first article, the Guardian published my follow-up. Freelance Programming Ltd. was launched. Over time it grew to 8,000 employees, and Dame Stephanie Shirley is now recognized as a pioneer of the British information technology industry. Here’s the follow-up article:

Computer women

In January of this year Mrs Steve Shirley was working quietly at home making up computer programmes in between caring for her baby and doing her housework. Now she has found herself the head of a company employing upward of twenty retired, home-bound programmers like herself. Like many businesses, it started in a very small way. When she retired from her job as a programmer with a big computer company, she was offered a few programming projects to keep her occupied at home. She could work at them in a leisurely fashion, enjoying the contrast between the stark, modern, technical world of computers and the idyllic charm of her cottage in the Chilterns. In this way she found a mental satisfaction that had not been fully achieved in caring for her home and family.

As her circle of clients widened, she was considering seeking out other retired programmers like herself who could help with the load of work. Then a Guardian article on programming as a career for women [my first article] brought in a flood of letters from women who were desperately needing something more stimulating to do with their time. Many were very highly qualified, but because of their children could not consider going back to a job that wanted them on an all-or-nothing basis.

There are some obvious difficulties in running a part-time business of this kind, and Freelance Programmers Ltd. is now having to face some of them. The first is one of organisation. To get a reasonable standard of efficiency, Mrs Shirley had to eliminate those applicants who did not have access to a telephone. The business is at present being run from the cottage, where the telephone rings at all hours of the day and night, and Mrs Shirley herself works very long hours keeping in touch with her staff. In order to get back herself to the part-time basis which would give her time for her family, she plans to open a central office. Here she would be able to employ a typist—at present she does the typing herself, or sends it out to one of her staff, thus making a two-day time lag. The office will be in an area where some of the staff are already living, and her plans are for a combined office and nursery suite, so that the mothers who come to the office will have the children cared for, but will be at hand if needed.

There will still be many of the staff working by themselves at home. Some of them are doing it because they need the money, but for the great majority it is a release from the pressure of four walls and a roof and a tedious round of housework. Mrs Shirley has proved that this method can be made to work, particularly for fairly short-term projects. A larger job, that might take perhaps two years to complete, she prefers to give to women less tied to family responsibilities.

She also needs more free women for the large amount of travelling and meeting clients involved in the business. An ideal staff member is a woman with no children, who is married to a schoolteacher. She had been unable to get a normal job because she wanted all the school holidays off to be with her husband, and not just the regulation three weeks. But for several months at a stretch she is free to go anywhere, do anything for the company.

It has become clear that an entirely homebound, part-time organisation will not work satisfactorily. But a group that is basically of this sort, with a leavening of more mobile staff and with an efficient central organisation, may well be a model on which similar groups of professionally trained women might be based.