Posts Tagged ‘women’s movement’

Time Magazine on women, 1972

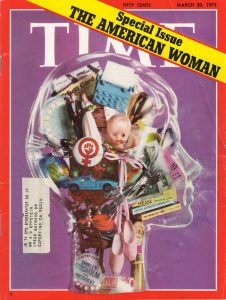

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

The issue starts, as usual, with letters to the editor. These are from female readers responding to the magazine’s invitation to “write to us about their experiences and attitudes as women, and to tell us how their views on this subject have changed in recent years.” I tabulate the responses. Twenty enthusiastic about the new feminism, three ambivalent, and six tending negative, arguing that, since very few higher level jobs are available to women, by going out to work they “trade the drudgery of housewifery for the drudgery of an office job.” Or, as another writer put it: “Rush out each day to that exhilarating, high-paid position; rush home to that hot-cooked supper (cooked by whom?); relax in that nice clean living room (cleaned by whom?). Most likely, dearie, you’ll hold down two jobs—‘cause when you get home from that executive job in the sky, there ain’t gonna be no unliberated woman left (and certainly no man) to do your grub work.” Sidebars titled “Situation Report” in the various sections of the issue reflect these caveats: prejudice is rampant against allowing women into higher paid or managerial professions.

Time’s editorial attempts to define “the New Feminism” as “… a state of mind that has raised serious questions about the way people live—about their families, homes, child rearing, jobs, governments and the nature of the sexes themselves. Or so it seems now. Some of those who have weathered the torrential fads of the last decade wonder if the New Woman’s movement may not be merely another sociological entertainment that will subside presently.”

Subsequent pages offer a history of the currents of social change that “have converged the make the New Feminism an idea whose time has come.” There are portraits of a range of American women, a piece on “the organizations, aims, difficulties and range of opinions that help make up Women’s Liberation in all its diverse forms,” a one-page snapshot of attitudes in Red Oak, a small Iowa town. Here’s a quote: “Many Red Oak women agree with Doctor’s Wife Jane Smith: ‘A woman’s place is in the home taking care of her children. If a woman gets bored with the housework, there are plenty of organizations she can join.’” A photograph shows Mrs. Smith entertaining friends at bridge. I have a flash of memory: one of my sisters saying the same words to me.

The “Politics” section of the magazine showcases some familiar names: Bella Abzug, Shirley Chisholm, Martha Mitchell, and describes the bipartisan effort of the National Women’s Political Caucus to get more women elected, or selected, as delegates to the Democratic and Republican National Conventions.

The “Science” section describes the difficulties a woman astronomer faced. As a woman Margaret Burbidge, who helped develop a new explanation of how elements are formed in the stars, “found that she could get precious observing time at Mount Wilson Observatory only if her husband [a physicist] applied for it and she pretended to act as his assistant.” The Burbidges also ran into nepotism rules at the University of Chicago. “’The irony of such rules,’ says Mrs. Burbidge, who had to settled for an unsalaried appointment while her husband was named a fully paid associate professor, ‘is that they are always used against the wife.’” I think of women scientists I have known who suffered the same exclusion, such as Beatrice Tinsley, a British-born New Zealand astronomer and cosmologist whose research made fundamental contributions to the astronomical understanding of how galaxies evolve, grow and die. Beatrice had to divorce her husband, a Texas University professor, and move to Yale to gain the position she needed to do her work.

In many science fields, recognition for outstanding women is still abysmally low. I think of efforts by my son David, a mathematician, to redress the paucity of profiles of eminent women mathematicians in Wikipedia.

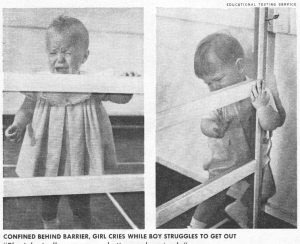

Section after section, the stories continue. “The Press” section is subtitled “Fight from Fluff,” how women’s pages are shifting to more general interest features. ”Modern Living” talks about efforts to find new pronouns, the opening of day care centers, and changes in marriage dynamics. The Situation Report for the “Law” section puts the number of women lawyers in the U.S. at 9000, 2.8% of the total number of lawyers. Of this small number, “less than 12% of them were making more than $20,000, as compared to 50% of the men.” Similarly depressing are statistics for recognition of women in the arts, in business, and in medicine. The “Behavior” section, which looks at research into sex-related differences in early childhood, seems to reinforce stereotypes: “Many researchers have found greater dependence and docility in very young girls, greater autonomy and activity in boys.” The accompanying pictures show two babies behind a barrier set up to separate them from their mothers. The little girl cries helplessly; the boy struggles to get out.

A keynote essay by Sue Kaufman, author of the novel Diary of a Mad Housewife, attempts to capture the feelings of a composite American woman, interested in the new ideas, admiring of feminist leaders, but cautious about jumping on the bandwagon. Kaufman describes an imagined scene: an admired leader is coming to town to speak. The woman arranges for a babysitter. “She will go, usually with friends. They will arrive … take their seats—and slowly it will begin to happen … she begins to feel the flickers and currents of a mass communion, a rising sense of excitement that she imagines parallels what one feels at a revival meeting … this powerful thing happening, this sweeping, surging, gathering-up-momentum feeling of intense camaraderie, solidarity movement.” After the meeting is over, Kaufman describes the woman driving home, paying the sitter, returning to the children and the kitchen “to take up the reins of her existence. Only—something is wrong. She is overwhelmed by a terrible sense of wrongness, of jarring inconsistency. There was that surging, powerful feeling in the hall, and now, stranded on the linoleum under the battery of fluorescent kitchen lights, there is this terrible sense of isolation, of walls closing in, of being trapped. …but she doesn’t burst into tears. …In spite of the desolation she feels, she knows that she is not alone…there is enormous comfort in knowing that. And knowing that is one of the big changes in her life.”