Posts Tagged ‘writing’

The persistence of hope

Reading through letters I wrote to my parents in early 1973, I am struck by how much writing I was doing, in spite of all the other stuff going on in my life.

January 10, 1973

(Having been laid off in an economic downturn, my husband was job-hunting.) Nothing new regarding our plans – I wish the thing was settled soon. …

I have been hectically busy for the past month or so. … This week I have been working on an outline of my novel, and polishing up several chapters for a grant-in-aid that is being offered by the San Francisco Foundation. Don’t have much chance of winning it, but less if I don’t enter! … I have a huge pile of papers to grade (my freelance job as a reader for a local high school), for which I shall have to read the textbook first; another reference book on the Indian rock drawings we visited at Tulelake (for an article); and a story to finish on the disposal of Christmas trees for which I have a go-ahead from a local magazine.

February 12, 1973

February 12, 1973

Finished today a short story based on our experience of buying a baby Christmas tree this year. We were going to give it to a park, but the kids wanted to keep it. The kids like the story, so I hope the women’s magazines will.

March 3, 1973

Our own plans are getting more finalized. Tony will be commuting between here and Santa Barbara for a few months … and then we expect to move south when the kids finish school in June. … but at least now I know what sort of time scale I have for finishing up projects here. I am currently working on a big story about the influx of older, traditionally brought up housewives into the women’s movement, and have several other ideas on file that I will need to get material for before we leave, As usual, every new idea spins off into several new stories, and I can’t possibly find time to do them all.

March 22, 1973

Tony leaves for Santa Barbara Monday, and I am going to drive the kids down later in the week for a long weekend of looking around and getting our bearings. … In the meantime I have a huge pile of students’ field trip reports sitting on my desk … and then back to the draft of a story that could be the most important thing that has happened to me career-wise. I have an invitation to submit to Harpers Magazine (and that is the top) a story on the women’s movement. My thesis is that the rapidly increasing numbers of middle-aged, middle-class housewives being attracted to the movement is having a significant effect on the direction of feminist politics. I have been very involved with the setting up of a chapter of National Women’s Political Caucus here, and have also got many insights from the Department of Continuing Education for Women at Foothill College, which is very active in encouraging frustrated housewives to get back into the mainstream of life.

Of course a go-ahead doesn’t mean the story is sold. I think I have learned a lot about this since last year, when I was so crushed that the famous publishing house which wanted to see my novel sent it back again. But still it’s exciting to have it even considered.

Where are they now, all these articles and stories I worked so hard on? Gone. Never published. Not even copies crammed into my old black filing cabinet. I must have thrown them out in a fit of tidiness, or more likely despair. I can’t even find the kind, hand-written rejection letter from the editor of the famous publishing house, which I know I kept for years. All that’s left is the memory of how hopefully we writers begin new projects again and again and again.

The place of art

What is art, and what place has it had in my life? This was the assigned topic for the first set of high school student essays I graded in my first paying job in California. In those days, the late 1960s, California schools had enough money to hire readers to relieve teachers of the time-consuming task of grading papers. I worked primarily with Millicent Rutherford, the Humanities teacher at Lynbrook High School, in the Cupertino Union School District. Over time, we developed a warm friendship.

I was saddened to learn that Millicent died last October, at the age of 91. Her obituary notes: “She will be remembered for her glittering sense of style, her sharp wit, and her boundless energy.” A 1991 Los Angeles Times article on remembering teachers who made a difference includes an anecdote by Stephen Bennett, CEO of AIDS Project Los Angeles:

“We’d study Italian art and [Ms Rutherford] would get . . . photographs from some of the Pompeian paintings that are not typically looked at—the parts of Pompeii they won’t show you because the graphics on the wall are what Americans would consider lewd. And she’d show up in a Pompeian red dress to start the day.”

To honor Millicent’s memory, I’ve been thinking about how I might respond to her essay topic.

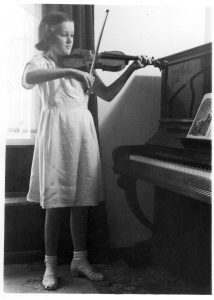

When I was the age of Millicent’s students, music was my passion. I played second violin in my town’s municipal orchestra. At my first concert, the orchestra tackled Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. It must have sounded decidedly amateurish. But the experience of being a part of that magnificent work, of sharing the language of music with my fellow musicians and with an audience, is a thrill that has always stayed with me.

Tauranga Municipal Orchestra at rehearsal in the high school assembly hall, c. 1952. I am in the front row, just to the left of the podium.

Painting too speaks a language without words. On the wall of my office is a reproduction of Georges Rouault’s “The Old King.” I saw the original fifty years ago, at the National Gallery in London. Friends I had come with moved to another room without me as I sat on a gallery bench, weeping. I still weep inside when I look at it.

Concerts, theatre, dance performances and visits to art galleries have always been a major part of my life. The written word has been my personal art form. To struggle with the lines of a poem, to convey emotional meaning through images, leads me to a personal answer to the question: “What is art?” For me, it is a way of sharing what is meaningful in our lives.

Inside a 1960s newspaper office

In graduate seminar at the University of Canterbury, Professor Neville Phillips fixed me with a stern eye as he returned my latest effort. “You are getting through your history papers, Miss Dinsdale, on your writing style, not on your knowledge of history.” I flinched, and worried. Graduation was coming up, and I planned to apply for a job on The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand’s morning newspaper. Within the next week or two I needed to ask him for a letter of reference. Not only was Prof. Phillips head of the history department, he was a former newspaperman himself, and still had deep connections at The Press.

I needn’t have worried. Not only did he write me a nice reference, he also penned a personal note to the paper’s editor, Arthur Rolleston (Rollie) Cant, that opened the door to my dream job.

Press Building, Cathedral Square, Christchurch, NZ. Photo by Michael Whitehead from

http://www.nzine.co.nz/features/150years_the_press.html

I had known since childhood that writing was what I wanted to do. Movies about newspapers such as While the City Sleeps (1958), Deadline – U.S.A. (1952) and Ace in the Hole (1951) filled me with fantasies about the drama and excitement of the reporter’s life. Here was my chance to prove myself.

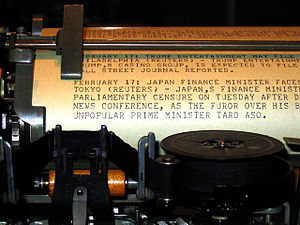

I loved working at The Press. A great Gothic pile on Cathedral Square, in the heart of Christchurch, the Press Building was a newspaper office out of one of those Hollywood movies: a cavernous newsroom that smelled of newsprint and dust, where telephones jangled, the chief reporter barked commands and the urgent clatter of the Teletype machine signaled a breaking story somewhere in the world.

Picture of Merganthaler linotype machines in a compositing room from the archives of the Nieman Foundation http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/

Sometimes I would be sent on an errand out back to the compositing room, a shadowy cave where enormous Mergenthaler Linotype machines made a deafening clatter. Deeper into the heart of the building, the throb and rumble of the great press itself, and the bustle of loading trucks in the small hours of the morning for long distance runs. When The Press celebrated its 100th anniversary in May 1961, its circulation was 62,000, with subscribers throughout the South Island.

It felt glamorous to work late into the evening, rushing back from meetings to meet the deadline for next morning’s paper. I shared dreams with the other young reporters, all of us with a few scratched notes tucked away for what each of us was sure would be the Great New Zealand Novel. We all had the sense of being part of an old tradition.

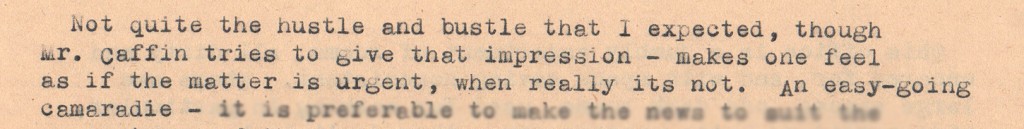

Among my notes I found this description of the office, written in 1960. Christchurch at that time was a sleepy provincial city of 193,000 people, and exciting news stories didn’t happen all that often.

I described the office as a jumbly assortment of rooms, all dirty and uncared for, and with space saving nonexistent.

I particularly appreciated my desk in the women’s department, by a window where I could gaze out across Cathedral Square. I’ve written about this view in an earlier post.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Going Dark

In 1966, my friend Diana Neutze developed multiple sclerosis (MS). She was not yet thirty years old.

I first met Diana about ten years before this, when we shared English Lit. classes as freshmen at Canterbury University in Christchurch, New Zealand. During school breaks we worked as kitchen hands at the same remote fishing camp. I was part of her wedding, and she of mine. We lived next-door to each other as young marrieds, and shared survival tips as penniless expatriate mothers of small children in London. Even after I moved to California and she returned to New Zealand, we stayed in touch as best we could.

For decades Diana’s illness came and went. She learned to live with it, devising ingenious stratagems for making sure she stayed mobile and independent. Whenever possible, she refused medications. All she had left, she said, was her mind, and her ability to find joy in music and the beauty of her garden. Painkillers took that clarity of mind from her, and this she could not allow. Right up until the end she was writing and publishing poetry. (I reviewed a recent book in these pages) I introduced her, via email, to a quadriplegic friend who got her started with voice recognition software. When she could no longer edit using one finger on a keyboard, or see to read, she dictated edits to a carer.

Diana and I traded poems and, as her body slowly but inexorably closed down, thoughts about death. She was in my mind when Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino invited local poets to respond to Wendell Berry’s poem “Going Dark” at a 2012 Winter Solstice event. I sent the poem to Diana, and included it in my new chapbook, Earthward. When I spoke to Diana via Skype in April 2013, three days before she died, she accepted my promise to dedicate Earthward, to her memory. At her request, my poem, “Going Dark,” was read at her funeral. Here it is:

Going Dark

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

— Wendell Berry

My friend’s body is a brown leaf,

shriveled and curled inward.

Pain is a constant, yet

the fierce flame of her will

refuses surrender.

It’s not death’s darkness she resists

but the loss of a self transfixed

by what is beautiful:

a Bach air, the light

through her walnut tree.

This dark she speaks of

has no scent of earth,

no draft from unseen wings,

no sudden rustle in the undergrowth.

What can I say to her, and to myself,

this season of gathering in

our lives against the rainy dark,

against the ancient fear

that light will not return?

Just this: a dry leaf

fallen to ground disintegrates,

becomes the food that nourishes

all that sweetly blooms and sings.

My chapbook Earthward is available from Finishing Line Press. The direct link is: https://finishinglinepress.com/product_info.php?cPath=4&products_id=2129

Some of Diana Neutze’s poems can be read on her blog site, Living With Multiple Sclerosis.

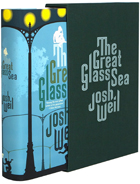

Josh Weil novel launched

I’m so proud of young novelist Josh Weil, whom Mendocino Coast Writers Conference picked as a rising star and invited to be on faculty at our 2013 conference. Here’s news from Josh worth sharing:

literary prize, the most incredible first-edition program I’ve ever seen, my complete book tour schedule—but there are two reasons, above all else, that this issue of The Gazette is a pretty special edition.

literary prize, the most incredible first-edition program I’ve ever seen, my complete book tour schedule—but there are two reasons, above all else, that this issue of The Gazette is a pretty special edition.“[An] impressive debut…As broad as its themes are—touching on political, philosophical and historical divisions—Weil’s first novel is rooted in family and fine storytelling; it’s an engaging, highly satisfying tale blessed by sensitivity and a gifted imagination.”

“A tale of longing and sadness, threaded by Russian folklore and heavy with the weight of love…resplendent and incandescent.”

“A well-timed dystopian tale, the novel beautifully details both the politics of [an] hypothetical Russia—“oligarchs bred beneath the clamp of communism let loose upon loot-fueled dreams”—and its impact on one small family.”

And the first newspaper review (out even before the official publication date!) was even better:

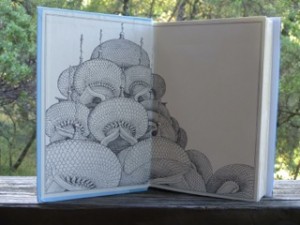

“If complex literary novels really are done for, Josh Weil must’ve missed the text message. His formidable “The Great Glass Sea” knits together strands of traditional Slavic folklore and futuristic speculative fiction to create a passionate reflection on technology and personal happiness. Spanning almost 500 pages, the novel poses mind-bending questions about politics, ecology and the ambivalent closeness of siblings…Weil pulls off dazzling strokes of storytelling…His distinctive voice obliges readers to slow down and swish certain passages around before swallowing…While keeping the sophisticated themes afloat (science vs. nature, the state vs. the individual, family obligation vs. ambition), almost every page flows with respect for the flawed, endearing heroes, Dima and Yarik. Pushing the envelope on literary artistry even further, each chapter begins with a pen-and-ink illustration by the author….A genre-bending epic steeped in archetypal stories, “The Great Glass Sea,” rises above the usual Cain-and-Abel formula by way of sensitive, resourceful craftsmanship.”

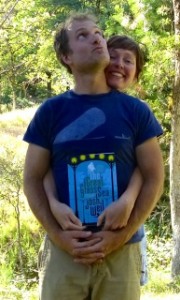

And here’s me, now, signing off and saying thank you, again, for continuing to care about what that tyke’s grown up to love, what the writer he became now does, these words on a page that I am so lucky to be able to share with you.

Doing by Not Doing

I thought I was retired from running the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference. But life happens, and so do medical crises. So I’m back as Acting Executive Director, scrambling to pick up the threads of all the detailed tasks that make up a successful conference and continue weaving them into a sweetly patterned braid.

I’ve done it before, several years of befores. My challenge is to keep calm, level-headed, unstressed. I know that to do my job well, I need to take time to do nothing.

This morning Tony and I took one of our favorite walks: from Laguna Point at MacKerricher State Park south along the cliff edge to Virgin Creek Beach, then footprints on smooth wet sand to where the water of Virgin Creek ripples and glitters as it crosses the beach to the sea. There we leave the beach and, picking up our pace, take the weather-beaten old haul road back to the Laguna Point parking lot.

This afternoon as I sit on my front porch, a white-crowned sparrow is singing from a nearby bush. Hummingbirds are working over the purple Mexican sage and yellow sticky monkey flower in front of me. I hear chirps from newly hatched Stellar’s jay chicks as a parent flies in to their nest in the wisteria vine. A violet-green swallow has come and gone from the porch corner cavity where they’ve sometimes nested. Two stems of dry grass dangle from the cavity. Not a good place this year. I warn them in my mind to beware the predatory jays.

Inspired by a talk a year or two back by Lewis Richmond, author of Aging as a Spiritual Practice, I am learning to meditate. It’s hard to push away the clutter of to-do lists, but I think I am making progress.

The mission of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference is to offer a place where writers find encouragement, expertise and inspiration. As executive director, my encouragement comes from the support and expertise of a wonderful team of volunteers, some of whom have been helping to run the conference for nearly all of its twenty-five years. My inspiration comes from the beauty of the pattern I braid from all these threads of tasks in my hand, its colors imbued with the memory of sea and headland, forest and garden, its thread tension even, unmarred by crises.

For the sake of all the writers who leave Mendocino Coast Writers Conference inspired by the supportive atmosphere the conference team creates, I can do this.

Texts

Searoad, a story collection by Ursula K. LeGuin, has a permanent place on my bedside table. It’s there because every now and then I need to reread a certain story. A very short story, less than three pages, it is titled “Texts,” and tells of an older woman who, bombarded by messages and calls to action, retreats to the coastal Oregon village of Klatsand for a month-long winter break. As she walks on the deserted beach, she notices that the waves have left messages in the lines of foam, messages she can almost decipher. The laciness of the foam leads her to speculate that crochet work and lace might also be legible. In a handmade lace collar she reads a message that seems directed to her: “my soul must go, my soul must go … sister, sister, light the light.” There the story ends, with the woman not knowing “what she was to do, or how she was to do it.”

I think of this oddly moving little story every time I walk on Ten Mile Beach, as I did last Sunday. The receding waves left undulating lines of bubbles, iridescent in the hazy sunlight, that popped to form patterns of foam. Scattered across the beach were strands of bull kelp, dried into coils and loops that lay like a cursive script on the sand.

Yesterday, when the wind was brisk and the sea streaked with white caps, I remembered an interview I did for the Mendocino Art Center magazine. It was part of a series I wrote on artists who helped found the art center in the 1960s. By the time I met Jim Bertram in the early 2000s, he was senile and nonverbal, so I had to rely on material in the art center archives for information about his background and artistic vision. Nevertheless, Jim and I spent a wonderful afternoon together. I think a poem I wrote at the time sums it up:

MESSAGES

For JB

“Line expresses the inner thought. It is a narrative of what we really want to tell each other but somehow can’t seem to verbalize.”

– Jim Bertram

These bright spring days, when the wind

scribbles its white calligraphy

on a wash of aquamarine,

I think of the artist in his studio

upstairs of a weathered storefront

overlooking Mendocino Bay.

Sheet after curling sheet he showed me, canvas

after canvas, covered with calligraphic forms

that could have been words, but were not.

In our shared silence I understood his drift:

how sometimes what matters most is inarticulate:

like the line of spray from a lifting wave,

the hand of an old man painting messages of love.

On my way downstairs from Jim’s studio, I fell in love with one of his paintings, which now has a place of honor in my house. I smile when I read its message.

Rain

This last month of our annual dry season, as grasses turn dusty brown and the trees droop, a phrase from a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem has been running through my head: “Send my roots rain.” This week the first good downpour broke the drought. I found and reread Hopkins’s poem, and recognized in it the cry of every writer who, like myself, goes through a dry spell and pleads for the rain of words and ideas.

Hopkins’s sonnet begins as a Job-like argument with God. He is angry that “sinners’ ways prosper” while he, a Jesuit priest who spends his life “upon thy cause,” sees his every endeavor end in disappointment.

The tone shifts in the second part of the sonnet. Hopkins points out the exuberant natural world:

See, banks and brakes

Now, leavèd how thick! lacèd they are again

With fretty chervil, look, and fresh wind shakes

Them; birds build …

He compares these images with his own struggles. He does not build, he says,

but strain,

Time’s eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes.

Hopkins sold himself short, of course. His poems continue to waken in the minds of later generations. But that sense of self-doubt is one all writers share. Whatever our spiritual beliefs, we can join in the prayer of Hopkins’s closing line:

Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.

You can read this sonnet, and link to other poems by Hopkins, at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/173669

Sweet Peas

The 2012 Mendocino Coast Writers Conference ended last night. This morning I picked sweet peas. Over my four-day absence to run the conference, the stems that had been in bud were in full flourish, and the row of pea plants sprawled even more rampantly over chard and carrots in my vegetable garden. I picked enough to refill vases of crumpled has-beens in my house, enough to give away to a friend, enough to fill yet more vases. I pressed my nose into the bouquet, sweet as the hugs of farewell and murmured words of thanks at the conference’s closing dinner.

The scent restored my faith in myself, both as the director of a successful conference, and as a grower of sweet peas. Back when I was a child in school, growing sweet peas was part of the curriculum, like spelling and arithmetic. Each year the Important Visitor would bring the signup sheet and reveal the wondrous names of new varieties. On Seed Day the visitor would return. Precious pennies would be offered up for hard black miracles. The visitor would give instruction in the mysteries of sweet pea growing. We must dig a trench two feet deep. The layer of compost in the bottom of the trench must be at least six inches before we shoveled back the dug and loosened earth. We must soak the seeds in water overnight, then plant exactly one inch deep, and four apart.

The best on Judgment Day took front row place at the flower show, a ribbon tucked beneath a jam jar that held three specimens, each with four blooms on a long stem. My jar sat humbly at the back. I was racked with guilt for shorted measure on the trench. The ground was hard, and my arms ached. My Dad’s compost pile yielded only a thin layer of partially composted weeds. I had tossed in some fresh grass clippings, but even those did not make up the required six inches. The seeds germinated, but the plants were spindly, and none of their flower stems boasted more than three blooms.

The guilt stayed with me all my life. Not enough my love for their bright beauty, not enough my penitence. I was cast down.

This year I decided to try again. A raised vegetable bed had an empty row next to a sheltered wall covered with a strong wire trellis. Remembering my past efforts, I figured that would be enough space. I dug in a bag of soil conditioner with an impressive ingredients list: composted firbark, chicken manure, earthworm castings, bat guano and kelp meal. I planted my seeds, an old-fashioned mix from Renee’s Garden, careful to places them one inch deep and four apart.

The seeds grew. And grew. I wound string from post to post to hold the plants against the trelllis. More string. A length of chicken wire that bulged and sagged. A couple of tomato frames. Soon I gave up. The chard was running to seed anyway, and the carrots were mature enough to survive the shade.

This morning as I teetered on a step-stool to pick the flowers, the thought came to me that their exuberant growth was akin to the joy conference participants were expressing. The Mendocino Coast Writers Conference has as its mission to offer a place where writers find encouragement, expertise and inspiration. This year it all came together. A brilliant group of faculty shared their expertise with participants dedicated to improving their craft, nurtured by a team of volunteers so cohesive that the flow of events was seamless.

Today we’re all exhausted and resting up. Tomorrow we start planning MCWC 2013.

A Lifetime of Friendship

“I have not written these poems, nor even read them; this is a spoken book,” declares my friend Diana Neutze on the back cover of her latest collection, AGAINST ALL ODDS. The title refers not just to her illness—she has battled Multiple Sclerosis for well over forty years—but to the difficulties inherent in transforming poems from her mind to the printed page. As MS closed down her body, she progressed from longhand, to one finger on the computer, to voice recognition. “But now I dictate to Gabrielle, my editing carer. Even the editing has been done by voice, backwards and forwards in the air.”

I was privileged to receive a copy of this handsome limited edition. Written over the past three years, the poems chronicle the poet’s recognition that her death is imminent and her determination to live each remaining day in the beauty of the moment. The poems are rich with images such as: …a tangle of branches/ peremptory against a crystal sky. She asks:

If I died tomorrow, what would

happen to the poems in my head?

Christchurch, New Zealand, where Diana lives, has suffered a series of devastating earthquakes and aftershocks that figure in many of the poems. In “Elsewhere” she writes:

…the earth where I thought

to lay my final bones

is writhing like a wounded snake.

The earthquake draws her mind outward to share a communal grief:

I mourn for the lost, the mained, the dead.

I mourn for our grieving city.

The experience of working with composer Anthony Ritchie on a song sycle of her poems draws her to a new awareness of the importance of people in her life. The final poem in the book reworks “Goodbye,” the final poem in the song cycle. Keeping the opening lines: If this day were to be/ my last …, she traces the trajectory of her preparations for death, from spiritual and inward-looking to a recognition of a fear in which …I relegated/ my friends to the outer suburbs. The poem ends:

If tonight were to be my very last,

I would be desolate

at leaving behind

a lifetime of friends.

I have been friends with Diana since our freshman year at the University of Canterbury, fifty-four years ago, where we met in English Literature class. During school breaks we worked as kitchen hands at the same remote fishing camp. We lived next-door to each other as young marrieds, and shared survival tips as penniless expatriate parents of small children in London. Over the years and across the globe we have stayed in touch, supporting each other as best we could in times of grief, commenting on each other’s poems, occasionally visiting. I honor this lifetime of friendship as I read AGAINST ALL ODDS.