Fingernails on glass

The visiting baby, almost two years old, sat alone and silent by the ribbed glass door of our row house in Egham, on the outskirts of London. He paid no attention to our chatty, energetic infant of the same age, nor even to his parents. Instead, he ran his tiny fingers obsessively over the ribs of the glass. Watching him as I fixed tea for our guests, I was uneasy.

A letter to my parents dated 20 April 1965 says nothing of this unease. Instead:

We had visitors on Sunday – Steve & Derek Shirley & their little Giles, who is the same age as David. We hadn’t seen them for quite a while, & had a very pleasant day.

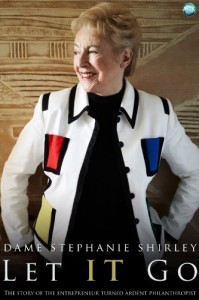

That was the last time we saw the Shirleys. Recently I have been reading Dame Stephanie (Steve) Shirley’s memoir Let IT Go, to try to understand what happened to our year-long friendship. The answer is devastating.

In early 1964 I had interviewed Steve by phone for an article that ran in the Guardian about women programmers and her new business Freelance Programmers. A few months later I gushed to parents:

30 April 1964

A couple of weeks ago we went to visit a very pleasant couple – the woman I interviewed (over the telephone) for my article on computer programmers. She has a baby the same age as David, and also works at home making up programmes – that is, the detailed instructions to be fed into a computer to do a required job. Anyway, we liked each other very much even over the phone, and she invited us to a meal to meet properly. They have a marvellous little stone cottage up in the Chilterns, right out in the country, with apple trees and daffodils, low oak beams, a huge log fire, and a grand piano squeezed into the front parlour. It sounds like a setting from a romantic novel, and that was the feeling even when we were there, that everything matched so well that it couldn’t be quite real. And a remarkable affinity too, between us as people. A bond to start with of course — it was the interest of her story that got me a place in the Guardian, and she credits me with the terrific boost to her business – she now has 20 other home-bound women working for her, and is forming herself into a limited company, and with giving her the confidence to get started. Then Derek is also a physicist [like Tony], reserved, very musical, and Steve and I found that our feelings and ideas agreed on all sorts of points.

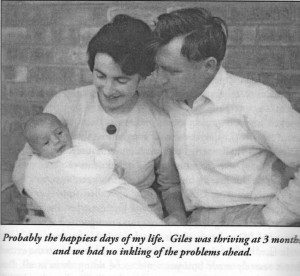

At that time Giles and our David were eleven months old. Steve writes in her memoir:

The catastrophe had crept up on us. It must have been in early 1964—when he was about eight months old—that we first began to worry, on and off, that perhaps Giles was a bit slow in his development: not physically, but in his behaviour. He was slow to crawl, slow to walk, slow to talk; he seemed almost reluctant to engage with the world around him. These concerns took time to crystallise—as such concerns generally do—and the first time I went to a doctor about them I couldn’t even admit to myself what was worrying me. …

My letters for the rest of 1964 are full of references to our new friends: visits back and forth, parties, conversations. In June I wrote: We liked them even more, if possible … isn’t it strange how people sometimes just click.

Meanwhile, Steve writes:

By the end of that year, however, there was no avoiding the observation that Giles was losing skills he had already learnt. … [He] had never become chatty. And now he fell silent. …

Months of desperate anxiety followed, in which there seemed to be little that we could do except fret. …

My lovely placid baby became a wild and unmanageable toddler who screamed all the time and appeared not to understand (or even to wish to understand) anything that was said to him…

By mid-1965 Giles had taken up weekly residence at The Park [the children’s diagnostic psychiatric hospital in Oxford] while the doctors there tried to work out what was wrong. Nothing I can write can capture the enormity of the sorrow that that short sentence now brings flooding back to me. …

Finally, in mid-1966, the specialists overseeing Giles’s case [at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children] delivered the devastating but unarguable verdict: our son was profoundly autistic, and would never be able to lead a normal life.

I understand now that our friendship with the Shirleys could not survive. Being with us would have been painful for them. There was too much unspoken, too much contrast between their child and ours. For a short time, we loved them. Even now, a sadness returns.

Postscript

Derek and Steve spent the rest of Giles’s short life seeking appropriate and supportive care for him. (He died at age 35.) Steve’s business flourished. She has poured her considerable wealth into philanthropy, primarily to support “projects with strategic impact in the field of autism spectrum disorders.”

Dame Stephanie Shirley: Let IT Go, Andrews UK Ltd., 2012

Alice, thank you so much for sharing about this difficult time. I know it’s been a long wearisome road that you and your family have traveled.

I can sympathize with any mother who has a child that is not really “Normal”. My daughter with now, secondary progressive Multiple Sclerosis, had a recent choking incident where she lost oxygen and had CPA applied.

After 10 days in the ICU at two hospitals, she has not returned to what was her baseline, or normalcy before this event.

In fact, I was told by one Doctor on her 7th day in ICU that I had two alternatives. Either I pull all her tubes of oxygen, feed, and 5 IV’s and LET HER GO, or get a trachyotomy.

I could NOT let that happen.

After moved to her Kaiser Healthcare ICU, she recovered enough to go have solid food and go home after 3 days. This Doctor was so much more positive. He stopped all the sedation, IV’s of steroids, and other meds and put her on a simple oxygen formula.

What can a mother do but prepare for her early death with Funeral Coverage?

So moving and devastating….thank you Maureen!

We can know someone so well and yet not know them at all. All the more reason to be generous with our affection, as you and and Tony were for as long as you were able

So sad! Thank you for writing this Maureen!

So sad and sweet

What a touching and timely memoir Maureen. There was much less public conversation back in those days about autism, or any other childhood/parenting experiences outside the boundaries of “the norm”. It takes a lot of courage for parents like Stephanie/Steve to share their situation.