Summer of 1967: an immigrant’s view

San Francisco, 1967. Sunday afternoon at Maritime Park. About twenty young black men sit on a low sea wall, bongo drums between their knees, thrumming an intoxicating rhythm. A crowd has gathered. Picnicking on the beach, my husband, children and I listen too, enthralled by the joyous sound. We have spent the morning exploring the old ships at the Hyde Street pier. Later in the day we explore the new tourist attraction of Ghiradelli Square.

In a letter to parents I wrote: … an old chocolate factory now converted into an arty plaza and shopping centre with fountains, outdoor restaurants, etc. … One of the most interesting places was the Children’s Art Centre – just a little gallery for exhibitions of children’s paintings, and free paper and crayons for any infant who felt like drifting in and drawing a bit.

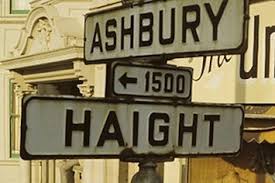

New to California, we had heard of the hippies in the Haight/Ashbury district, so on our way home to Cupertino we detoured along Haight Street. Sure enough, we passed storefronts with funky signage, long-skirted young women with hair held by braided headbands, long-haired and bearded young men in tie-dyed tee-shirts, a group playing music on a corner. Like travelers viewing exotic fauna, we gawked and drove on.

It is only now, looking back, I realize how little we understood of what we were seeing. The flower children who poured into San Francisco in what is now known as the Summer of Love were an eclectic group, revolutionary in their rejection of consumerist values, opposition to the Vietnam war, and embrace of free love, drugs, art and music. But this counterculture had a historical context, and this as immigrants we did not possess. I remember where I was when I learned in 1963 that President Kennedy had been assassinated. Like my English neighbors, I was shocked. But I did not experience that communal sharing of grief my American contemporaries remember. On British television I saw newsreel images of civil rights marchers being attacked by snarling dogs, fire hoses, and baton-wielding cops. But that was in some barbaric, far-off country. From the BBC news reports about Vietnam, it was obvious that American military involvement was a disaster, bound to fail as the French had before them. I’d not yet grasped the deadly impact of the draft on young American men.

Over the decades that followed our first summer in the US, I gradually filled in my knowledge gaps, mainly through snippets of personal information: a teacher who dodged the draft by moving to Canada, a veteran who came back from the war physically and psychologically maimed, a man who as a student registered voters in the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, a doctor and his poet wife who were cast out of their New England village because of their opposition to the Vietnam war. I took part in fair housing studies, and learned first-hand the effects of racism. I read histories of the period. But there has always been for me a sense of distance, a sense of being an outsider when my contemporaries discuss the experiences of their youth. I believe this sense of distance is true of all immigrants who come to this country as adults. Try as we might to ‘become Americans,’ we simply cannot share in the memory of those collective experiences that have shaped the early lives of our American-born neighbors and friends.

However, it has been fifty years since our arrival as new immigrants, since that summer of 1967. Over the years, new national crises and issues have unfolded. We have reacted to them, talked about them with friends, shared in community actions. We learned to belong. We too have finally become part of the American story.

Bravo, Maureen! Thank you for revisiting this time and sharing your insights.