A Language to Hear Myself

I started writing poetry in the fall of 1968. I know the date because that was the year my elder son started kindergarten and his two-year-old brother still took afternoon naps, so I had one hour to myself for the first time in five years. I chose poetry partly because it was a short form. An hour would be time, I figured, to write a line or two, or polish an image.

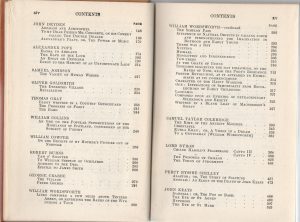

To write well, one needs also to read. I looked around for models. Educated in New Zealand, I had little acquaintance with American poets, and even less with work by women. (The table of contents for my college English I poetry anthology, The English Parnassus (Dixon and Grierson: Oxford 1909), contains no female names.) However, by 1968 I was already becoming acquainted with feminist ideas and literature, such as Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Over the next few years, I sought out female poets.

Anne Sexton’s work immediately caught my attention. Never before had I read poems so uninhibited in their exploration of female sexuality, mental illness, and the constraints of a conventional domestic life. I was particularly excited by Transformations, Sexton’s retelling of well-known tales by the brothers Grimm. Here’s the last stanza of “Cinderella:”

Cinderella and the prince

lived, they say, happily ever after,

like two dolls in a museum case

never bothered by diapers or dust,

never arguing over the timing of an egg,

never telling the same story twice,

never getting a middle-aged spread,

their darling smiles pasted on for eternity.

Regular Bobbsey Twins.

That story.

Sexton’s retellings bring out the essential unfairness of the old stories’ patriarchal viewpoint. Remember “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” in which an old soldier, having found out the secret of the princesses’ worn dancing shoes, gets to marry his choice of the young women? Here’s Sexton’s wedding scene:

…the princesses averted their eyes

and sagged like old sweatshirts.

Now the runaways would run no more and never

again would their hair be tangled into diamonds,

never again their shoes worn down to a laugh …

Another poet whose books are well represented on my shelves is Denise Levertov. As well as being a beautiful nature poet, she was a passionate protester of the Viet Nam war. This from “The Distance:”

While we are carried to the bus and off to jail to be ‘processed,’

over there the torn-off legs and arms of the living

hang in burnt trees and on broken walls

She also wrote of domestic tasks, such as in this opening stanza of a poem about a visit to her aging mother:

Milk to be boiled

egg to be poached

pot to be scoured.

Many other books by women poets of that era still grace my shelves: Audre Lorde, Sylvia Plath, Marge Piercy, Adrienne Rich, Diane Wakoski, to name a few. A recent exhibition of early feminist poets in the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library collection takes its title from a stanza of the poem “Tear Gas” (1969) by Rich:

I need a language to hear myself with

to see myself in

a language like pigment released on the board

blood-black, sexual green, reds

veined with contradictions

The exhibition’s introductory text by Audre Lorde sums up how I felt as I discovered the feminist poets of the 1960s and ‘70s:

For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is the vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we give name to the nameless so it can be thought.

I love that phrase – a language to hear myself – isn’t that what we do? Write when no one else will listen or can hear. What a blessing this writing is.

I wish I was as eloquent as Judith Pogue’s comment, above…. but alas I am not. I so appreciate your words, Maureen, because they cause me to stop and think….”oh yes, I know that feeling…” Many thanks.

Lovely to be reminded of those ‘outlaw’ feminists!

Thank you for so frequently paving my way to important insights.